Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

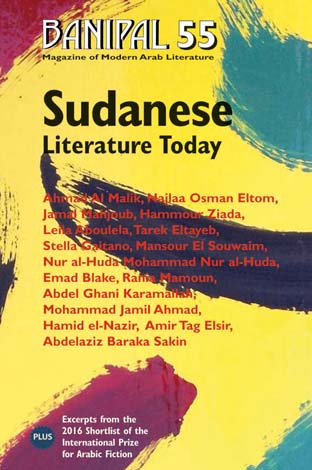

BANIPAL 55 – SUDANESE LITERATURE TODAY

We start Banipal’s nineteenth year of publication with a sharp eye on the essential character of the contemporary Arab literary scene. While much of the Arab world is plunged into chaos with wars and devastation, sectarian divisions, repression and censorship, the Arab literary side of life remains essentially modernist, secular, progressive and enlightened, speaking out for the marginalised – and needing to be heard across the world. In response to this, for the first time in our history, almost the entire issue has been given over to voices of writers from Sudan, with further translations and articles available online on our website, and more to be continued in the Summer issue.

Long months of preparatory work, volumes of emails, Skype conversations, working with authors and translators, locating umpteen works – novels, short stories, and poetry – have led to this issue on Sudanese Literature Today. Like our earlier features on the little known literatures of Yemen, Tunisia and Libya, we look forward to Sudanese literature in translation finding new audiences around the world, particularly through the encouragement and promotion this issue gives. Over the last few years Sudanese writers have been crowding onto the Arab literary scene in increasing numbers, making headway in several pan-Arab literary projects and prizes. With the majority of them living out of the country in the Arab Gulf or in Europe, they are creating almost a virtual Sudanese literary scene, one that cannot be silenced or censored.

We open with a short introduction by Ahmad Al Malik that immediately focuses attention on the fact that writers are finding new openings for sharing their work “despite the formidable hurdles”, which include routine “confiscation of books and newspapers” and the closure of most cultural venues. Emad Blake writes for the feature on “The New Novel in Sudan”, looking back at its pioneering writers of the mid-20th century, with Tayeb Salih’s now classic novel Season of Migration to the North, then to the particularly slim period of the 1970s to 1990s, and on to the millennium, when the Sudanese novel has “flourished in a spirit of openness and true revolution”, even though many are writing from outside the country. That spirit is certainly present in the fiction and poetry of the pages of the issue.

Hammour Ziada has an intriguing story about how a village learns tolerance and living with difference after Bedouin incomers arrive at the town, to the initial consternation of the village sheikhs. Ziada has the knack of creating suspense and atmosphere, allowing the story to unfold with small incidents building a picture that is visual and dramatic. There is more suspense, or surprising twists in the tail, in a short story by Ahmad Al Malik, whose central character, an old policeman, finds an unusual place to hide a stash of money from a thief. In a story by Leila Aboulela, her character Maryam is rightly happy, in the end, to be thwarted in her plan to violently avenge her father’s death. Both these stories look at weaknesses of human nature and ways of counterbalancing them.

There are a few works whose main characters are children, and one written for children, that we had to include, which is a salute to science and the natural world, “The Jealous Star” by Abdel Ghani Karamallah, in which a star complains of the attention the moon gets and convinces all the stars to leave the night and go to daylight – with unexpected consequences! Tarek Eltayeb’s short story about young disabled Helmy Abu Regileh and his football-mad friends, who find ways of playing truant, but who fear their mums’ clever questioning as to their whereabouts, has a wonderful mixture of panicky schoolboy bravado between the boys and politeness towards the mums. The chapter from Emad Blake’s novel Shawarma is a tantalising glimpse into the tale of a young boy, run away from home, whom we first meet perched on the roof of a railway carriage, along with dozens and dozens of others, the whole length of the train, clanking its way to Khartoum through the vast and varied countryside with its rich cargo of characters on top. Rania Mamoun is an experienced storyteller and her story “Passing” is an elegy to the loss of a dear father, as the protagonist daughter is struck by memories and taken vividly back to the very moment of her father’s passing.

There are but two poets in the feature: Najlaa Osman Eltom, who transports the reader into Maryam’s aching sorrows and a moment’s walking in a crowded, hot street; and Mohammad Jamil Ahmad, who in a series of short poems presents stark images of silence, the absolute, secrets untold and ancient whispers.

The chapter from Hamed el-Nazir’s historical novel The Waterman’s Prophecy recounts how a community of maligned and abused former slaves works to break away from their slave-owning families and establish an independent community in the village as good neighbours. Their leader, the waterman, explains that “only love is capable of defeating injustice, disparities and grudges”.

Jamal Mahjoub brings readers back to reality with the disturbing account of how Dr John Garang, inaugurated as Vice-President in Sudan’s 2005 Government of National Unity, met an untimely death in a helicopter crash, ending the hopes of many for a single unified country. Stella Gaitano was born in Khartoum, studied pharmacy at the University and became a writer; it used to annoy her that people always introduced her as “the Southern writer who writes in Arabic”, when she was just a writer. She writes about her struggle to deal with Sudan’s warring sides and her forced move to South Sudan when the country partitioned, ending with the question we can all ask: “Aren’t we in the throes of an insane drowning?”

The anti-hero of Mansour El Souwaim’s novel A Rogue’s Memory is more than a misfit, he’s wickedness itself, symbolically bad from birth with legs withered and inert; Adam Kusahi learns hard and fast, charms the hookers and deceives the superstitious for easy money, but also feels great compassion, friendship and love. In this chapter he relives his early life with his solvent-sucking mother, her gruesome death, begging with street girls, learning to read and write, and begging for coins on a traffic island at a busy junction – they called him Kusahi the King.

One of the obstacles for Sudanese writers is the state of publishing in the country. In an exclusive interview, the major Sudanese publisher Nur al-Huda Mohammad Nur al-Huda, head of Azza Publishing, explains candidly how the problems he faces of high costs, lack of modernisation in the printing industry, random banning of books by the government, alongside lack of libraries and “worsening illiteracy and poverty”, are compounded by Sudan being “the greatest consumer of counterfeit books”, which are “sold for half or even one third” their prices. He laments the fact that from the governnment there “is no real will to develop people through knowledge acquisition”, but also says that the Sudanese reader is changing and that “the novel has jumped to first place and become the most read genre”.

There are also reviews of work translated into German, French and English: Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin's novel Der Messias von Darfur (The Messiah of Darfur) translated into German; Nouvelles du Soudan is a collection of short stories translated into French; and there are reviews of two novels by Amir Tag Elsir, Ebola '76 and French Perfume, published in English translation.

We are pleased to collaborate with the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in presenting translated exceprts of the 2016 shortlisted titles for this year's prize which will be awarded on 26 April.

Khaled Hroub pays tribute to the late Fatema Mernissi, with excerpts of his tribute published in the issue, and the full tribute available on the website.

April 2016