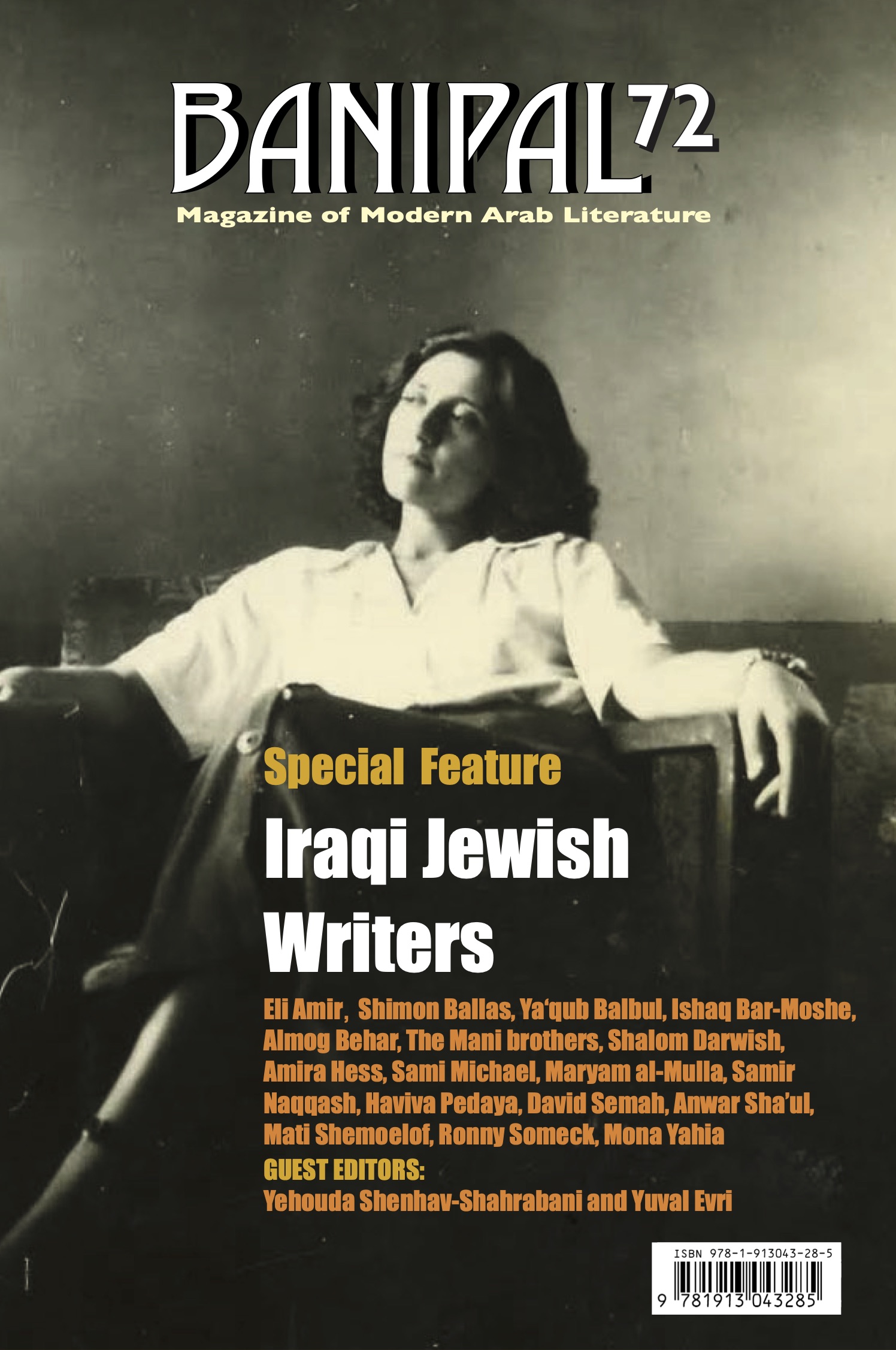

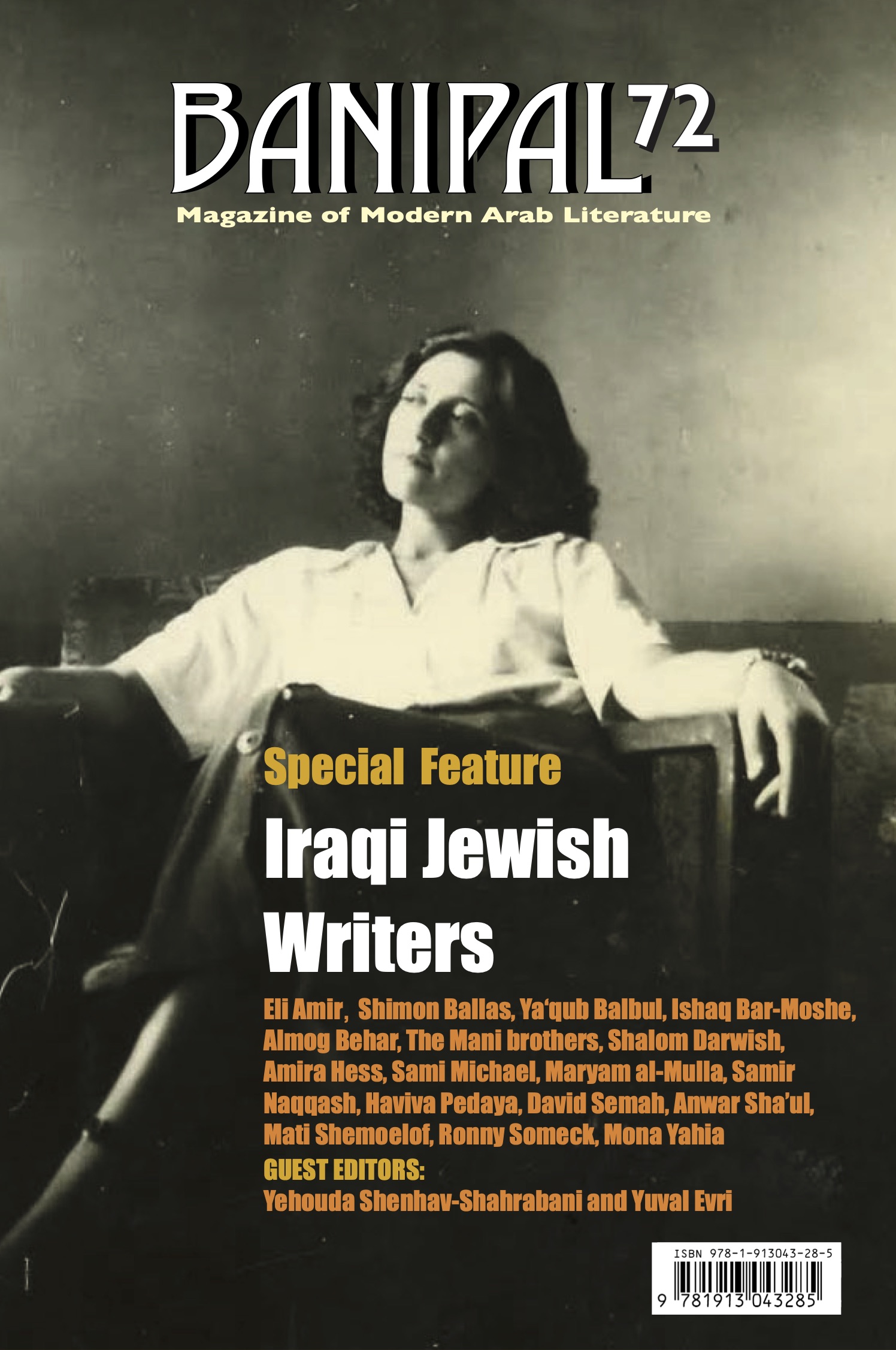

Banipal 72 – Iraqi Jewish Writers

Banipal 72 – Iraqi Jewish Writers

This unique feature on Iraqi Jewish writers includes short stories, excerpts from novels, and poems by 17 authors, all of Iraqi descent and of different generations and languages.

For several centuries, Iraqi Jews were key contributors to Iraq’s rich social and cultural tapestry – active in all areas of life as novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, musicians, composers, singers, and artists. Sadly, all this came to a tragic end with the massive transfer-emigration and forced displacement of Iraqi Jews in the 1950s to Israel.

The texts and introductory essays about the authors and poets raise universal questions of belongingness, exile, diaspora, cross-national affinities, and cross-linguistic possibilities – all were either translated directly from Arabic or Hebrew, with one written originally in English.

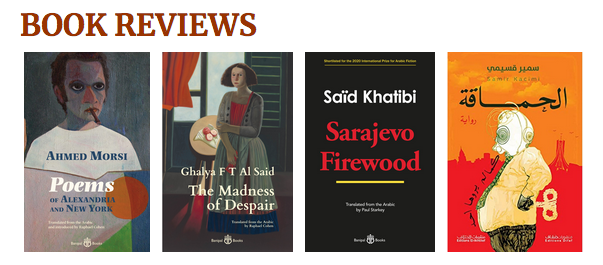

A taster of what's in the issue

Shimon Ballas

That said, my childhood days were also buzzing with other, far more pleasant sounds - the chiming of bells. There were a great many churches in the neighbourhood and their bells would chime daily, at regular intervals, summoning the worshippers for prayer services. I knew the chiming of those bells and could recognise each and every one of them. The big Catholic church bell’s ringing was as heavy and lumbering as the priest’s own march to the pulpit. In contrast, when the Armenian church’s miniscule bell chimed, it just about managed a thin, timid ringing. At New Year’s, Easter, and other Christian festivals, the chiming of the bells would cause the glass windowpanes to shake, leaving me feeling unnerved and elated in equal measure. Then there were the times when a single, solitary bell would chime sombrely at an unorthodox time of day. I would then know that a funeral procession was making its way to the church.

Countless funeral processions passed by our window. The first to emerge, as they turned into the cul-de-sac were the teenage boys in their pristine white gowns, holding candles; behind them came the priests in their black robes, and in the very centre – the priest leading the procession. Behind them were the pallbearers, and behind them, the family, and their companions. All sounds of praying would cease the moment they entered the cul-de-sac and were not heard again until they had finished crossing it. They advanced in silence along the cul-de-sac; with the coffin, bearing the smallest statuette of the Crucified One on its lid, suspended in the men’s arms. Passers-by stopped in their tracks, Christians made the sign of the cross on their faces, while Jews and Muslims watched the procession – their heads bowed.

. . . from The Imagined Childhood – an autobiographical story

__________

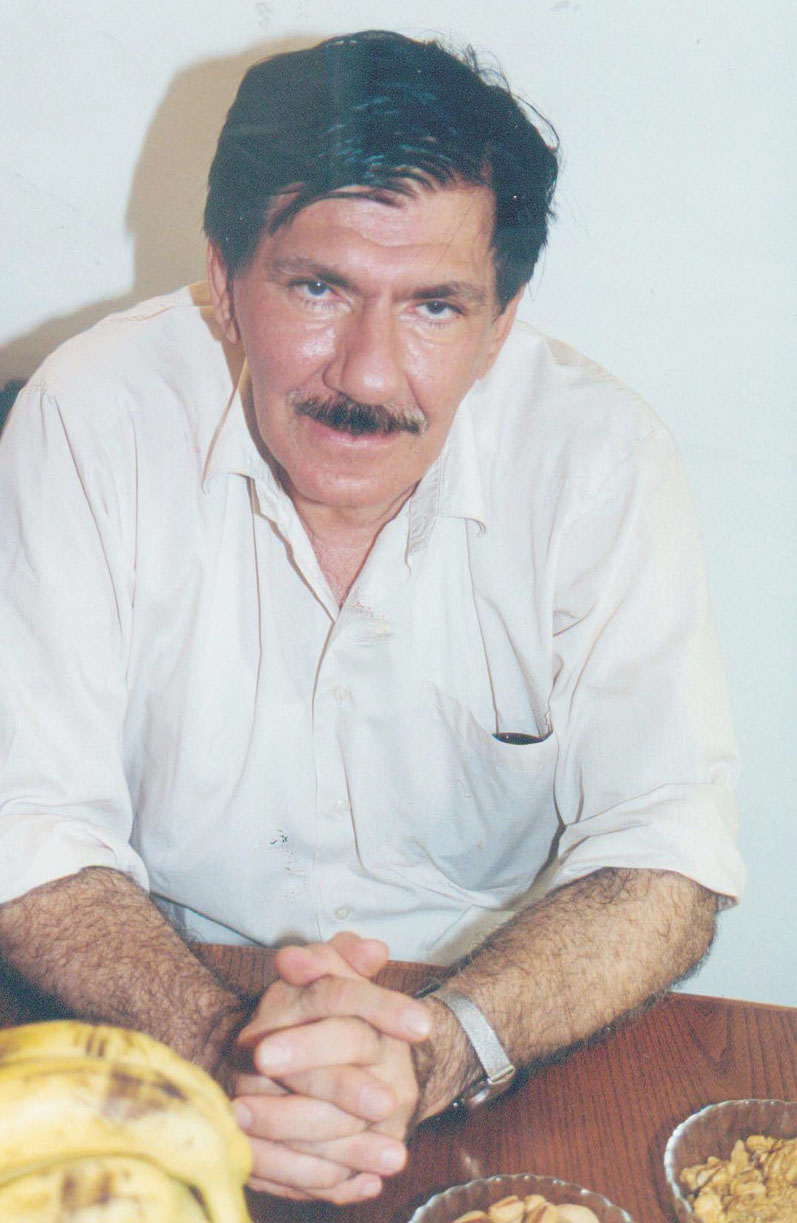

Sami Michael

“The next day we went out, our cart brimming with cold, tasty fruits. The sabra pears sparkled like shiny, red eggs. Then, after only two hours had passed, the officer approached the cart looking as if he were death itself incarnate. As soon as his grisly mug caught my eye, I told myself, ‘Ezra! Keep away from this man’s wickedness and head to another part of this big city, where he can’t see you and you can’t see him.’ I took the reins of the donkey, pushed away the hungry customers, and with one quick turn fled the scene. But the officer followed me… And why do I go on and on about all this? Because that very day they confiscated the fruit, the cart, and the donkey too! And just like that, they robbed us of our livelihood. I begged them to confiscate me instead and to release the donkey and the cart so that my wife and children could still find a way to live. But it was as if they were deaf… So, we moved from the deserted orchard to here in front of City Hall and we won’t leave until they return our cart and donkey to us… I’m not even bothered about the pears!”

Just then, the police officers managed to break through the crowd and reach Ezra. When they placed their hands on his shoulders, the crowd called out with rage: “Let him go! Let him go!”

A boy who stood on the tips of his toes, craning his neck, cried out: “Gestapo!”

. . . from Blessed is the Lord – a short story

Amira Hess

Salima, you’re still tearing up there by the fridge with the block of ice over

my eyes.

This was in the tin hut.

No great and terrible guiding wizard comes for me,

my spirit nailed in, lest it flourish.

I stood next to you, Salima, and a night at the migrant camp flew by us like a heavy shadow.

There are nights when the memory of cacti pricks at the tongue and the body

for I have tasted the forbidden sabra fruit.

. . . from the poem How Long Must We Be Remade

__________

Maryam al-Mulla

“He who knows, knows and he who doesn’t know, a handful of lentils.”

‘Amir was arrested, put in jail and sentenced to a number of years’ imprisonment. He couldn’t bear the disgrace, and the years of imprisonment were very hard for him and his family. On the day of his release from jail, the members of his family received him, but Nahiya was not amongst them. When ‘Amir asked about her, his wife said that his daughter had died a number of months after his being jailed. He smote his face, tore his clothes as a sign of mourning, and began to shout: “Nahiya is dead while the criminal wanders about freely.” When his wife asked him who the criminal was, he replied: “He who knows, knows, and he who doesn’t know, a handful of lentils.” And from that time on, he recited that proverb.

. . . from His Tragedy, a Proverb – a short story

__________

Ronny Someck

With the same chalk, a policeman marks a crime scene corpse

I mark the boundaries of the city where my life was shot.

I interrogate witnesses, squeezing drops of Arak

from their lips, and mimicking the dance moves of

pita bread over a hummus bowl with some hesitation.

When I am caught,

they will take one third off my sentence for good behaviour

and incarcerate me in the hallway of Salima Mourad’s throat.

In the prison kitchen, my mother will be frying the fish that her mother

had pulled out of the river waters whilst recalling the word ‘Fish’

emboldened on a massive sign in front of this brand-new restaurant.

. . . from the poem Baghdad

__________

Samir Naqqash

“Are you from Baghdad?” the man asked.

“In a sense. An Iranian Kurd flung into Baghdad by compelling circumstances years ago.” I replied.

We both nasalised the Arabic Baghdadi dialect we spoke. I knew where my nasal twang came from. What about his?

“Decades ago, my family left Baghdad for Bombay, where I was born and where I have been living since,” he started. “But no matter how far from Baghdad we lived, we were still Baghdadis. My extended family is in Iraq,” he added proudly.

“Were you visiting?” I asked curiously.

“A visitor and pilgrim,” came his answer. “I made the pilgrimage to Prophet Haskell, Ezra El Soufir, Priest Yehoshua, and Prophet Yona.” He paused a bit before adding: “Yes, we live there, but our hearts are forever in Iraq.”

. . . from the novel Shlomo the Kurd, Myself and Time

__________

Eli Amir

Nuri felt quite embarrassed by these visits. He knew full well what the other kibbutz members and their children thought of his father and his dress sense. At times, he would take pride in him, though he mostly felt shame. And as if his outfit weren’t bad enough, his father would often hum those Arab songs that made up the soundtrack of his soul, and would speak to his son in Arabic – in this place – where Hebrew is effectively canonised, and where everyone is expected to check their native tongue and culture at the gates and adopt this new Israeli way of life. There was the patriarch, out and about in the kibbutz, exploring the area; his fingers rolling some misbaha beads behind his back as if he were there on behalf of some Baghdadi Rothschild-esque baron, or the actual baron himself who, somehow, had wandered off and ended up somewhere unbecoming of his stature.

Indeed, Nuri dreaded his every visit. Every day, he would be put to the test and failing was not an option. He could not disappoint and had to prove himself with every challenge thrown at him. He shared general tales of kibbutz life with his father and would volunteer just a little bit more information when discussing his own day-to-day life, his studies, and the local social and culture scene. Today, too, he was telling his father how, even after three years of living in the kibbutz, he was still learning to wrap his head around this new world he has discovered, and of all his efforts to find out more and more about it, getting to know the people who had left their colder climates to move to this valley which, in the summer, becomes a proverbial furnace. When his father replied, he spoke in broken, half sentences and odd, random words that would not coalesce into a coherent statement. It seemed as though he were trying to articulate some things that had been weighing heavy on him. Nuri, too, was reluctant to let his guard down and share what was in his heart, keeping his doubts and dreams close to his chest.

. . . from the novel The Bicycle Boy

__________

Anwar Sha'ul

One morning, out of nowhere, my heart awakened, and the lyrics ceased. I moved forward on my path, at times walking indolently, and at other times running and gasping for air. I felt that I had found my Unknown Other in the stunning, serene, and shy Bella. Her smile was the secret behind her allure. Her smile was her divine gift with which she mesmerized and smote the minds of her admirers.

I fell head-over-heels with that smile, falling so hard for the woman that a mystical relationship, like that of a Sufi towards God, eventually grew. However, I fear this love might have been unrequited on her part. The first time that smile shone and caught my eyes was in a club, then in a park, and then a pathway. Finally, it dawned once again on a school stage, where she was called Bella, the one with the radiant smile. I wrote my poem “Smile to Me!” for her:

Smile to me!

Give me that smile for in it resides radiance

Whose gleam drowns the darkness of despair.

Smile to me for there is charm in it

That always seeps deep to my soul.

Smile to me like a bright star

To cast out memories today and yesterday.

Oh, daughter of light, with that radiant smile

that gives forth like the rays of the sun.

Your lips enflame the passions of the heart

and inspirits the whims in each sense.

Almighty Allah refined these lips, then declared:

“Let thy glow be part of my godliness.”

. . . from Me and the Unknown Other Half: Which of Us Sought the Other?

__________

Plus works

by Ishaq Bar-Moshe, Shalom Darwish, Almog Behar and Mati Shemoelof never before in English translation, as also by Mona Yahia, with introductory essays by guest editors Yehouda Shenhav-Shahrabani and Yuval Evri, and by Ammiel Alcalay, Reuven Snir, Haviva Pedaya, Lital Levy, Ryan Zohar, Orit Bashkin, and others.

Translations by Eran Edry, Uti Horesh, Hana Morgenstern, Aviva Butt and Reuven Snir, Zeena Faulk, Ryan Zohar, Jonathan Wright, and others.

PLUS