Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

In addition to Stephen Watt's full review below of Adonis: Selected Poems, which appeared in Banipal 41, we are happy to include additional texts on Adonis's works which could, unfortunately, not be squeezed into the magazine.

Please click on the link to go straight to the section

On translations of Adonis in

the UK

A Brief Bibliography of Adonis in Translation

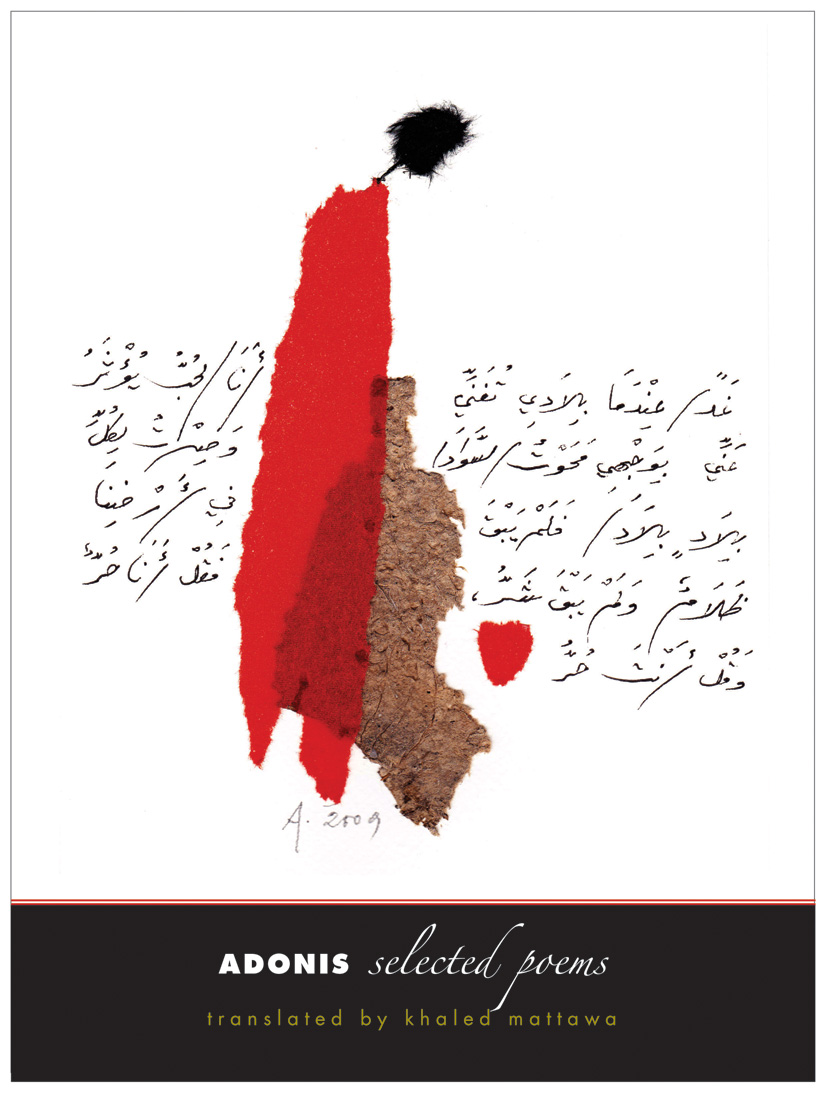

Adonis: Selected Poems

Translated by Khaled Mattawa

Yale University Press, New Haven and London

Hbk, 401pp. ISBN 978-0-300-15306-4

The

Human is the Poetry of the Universe

“The

word in poetry must transcend its essence, it must swell and include more”

As befits a poet of his name, the span of

Adonis’s work – the parabolas of his vision – carry over great distances, both of

space and time, or more accurately they dismantle such distances and

boundaries. His is a poetry charged positively to unsettle the ideas of his

readers. The roots of his work are pre-Islamic, pan-Mediterranean, and

post-modern. Almost from his first published poems, and certainly from the time

he took on the name Adonis he adopted the qi’ta

or fragment as a base unit for his language and thought and of his

poetics. He has constantly, but never monotonously, created and fashioned short

lyrics, sequences of linked lyric fragments, long melted collage poems running to

ten, twenty, fifty pages and book length ‘epics’ spanning volumes: all utilise

the fragment as basic unit of breath, rhythm, colour, sense and meaning. His

breakthrough and commitment to vision were clear in other ways from very early

in his life of writing: the collaboration with Yusuf al-Khal on Shi‘r – almost certainly the most influential and

radical (in the sense of making its readers come to terms with their cultural

rootedness) of modern Arabic journals; his work as founder editor of Mawaqif from 1968; his multi-volume anthology of two

millennia of Arabic poetry, first published in 1964; the two-volume analysis of

Arabic literature that he published in 1973 Al-Thabit

wa al-Mutahawwil (whose very title, roughly ‘The fixed and the

changing’, sums up his struggle); the many volumes of classical and

contemporary poets that he edited. All form part of his endeavour to reinvent

language and poetry and reinvigorate contemporary Arabic.

His third book of poetry The Songs of Mihyar of Damascus marked a definitive disruption of existing poetics and a new direction in poetic language. In a sequence of 141 mostly short lyrics arranged in seven sections (the first six sections begin with ‘psalms’ and the final section is a series of seven short elegies) the poet transposes an icon of the early eleventh century, Mihyar of Daylam (in Iran), to contemporary Damascus in a series, or vortex, of non-narrative ‘fragments’ that place character deep “in the machinery of language”, and he wrenches lyric free of the ‘I’ while leaving individual choice intact. The whole book has been translated by Adnan Haydar and Michael Beard as Mihyar of Damascus: His Songs (BOA Editions, NY 2008) and thirty of the poems are also included in Mattawa’s Selected Poems. In a sense this book also is a single long poem and while each part stands on its own the separate poems can prove slippery to quote from when isolated. Haydar and Beard’s translations are richer, more expansive, Mattawa’s concise and more curt. Both work very well.

The former has, in triplet stanzas: “Mihyar is king, / a king whose dreams are palaces / meadows aflame. / Just today, words / heard complaints against him / from a voice that died. / Mihyar, a king. / He lives in the dominion of the wind / and rules in the land of secrets.”

Mattawa has “King Mihyar/a sovereign, dream is his palace and his gardens of fire./ A voice once complained against him to words/and died./King Mihyar/lives in the dominion of the wind/and rules over a land of secrets.”

Adonis is here marking out concerns that echo throughout his work and addressing sources of inspiration that are constant. The elegies of the final section – for Abu Nawas and al-Hallaj among others – foreshadow celebratory poems, to Abu Tammam and al- Ma‘arri, of thirty years later.

In 1970 Adonis published A Time Between Ashes and Roses as a volume consisting of two long poems ‘An Introduction to the History of the Petty Kings’ and ‘This Is My Name’ and in the 1972 edition augmented them with ‘A Grave For New York.’ These three astonishing poems, written out of the crises in Arabic society and culture following the disastrous 1967 Six-Day War and as a stunning cri de coeur against intellectual aridity, opened out a new path for contemporary poetry. The whole book, in its augmented 1972 edition has a complete English translation by Shawkat M. Toorawa as A Time Between Ashes and Roses (Syracuse University Press 2004) while Mattawa includes a translation of ‘This Is My Name’ in the Selected Poems. In ‘An Introduction to the History of the Petty Kings’ (itself echoing themes from the ‘petty times’ of Mihyar) Adonis fragments, brackets and slashes prose and verse lines and uses ‘etc.’ both to convey exaggeration and hubris and to embody the sense of despair. His language remains lyrical – recreation of the lyric in the face of turmoil being one of the poet’s great qualities:

“A child stammers, the face of Jaffa is a child / How can withered trees blossom ? /

Here the slashes (/) are an integral part of the poem’s language, there to embody as language how lives are cut short or interrupted. As the 28 sections of the poem draw to their end, the poet repeats the fragment “In a map that extends . . . etc.” and states the huge rifts between life and language in very exact fragments: “This language that suckles me, betrays me /” . . . “Here is the gazelle of history opening my entrails /” and, tellingly, “The beautiful storm has come but not the beautiful devastation.” But there are notes of hope. He emphasises that “I am not alone” and says:

“A time between ashes and roses is coming

When everything shall be extinguished

When everything shall begin.”

Khaled Mattawa provides a genuine overview of the span of Adonis’s work in Adonis: Selected Poems. The only major book that he does not include any part of is the monumental Al-Kitab which, running to three volumes, it seemed sensible not to try to excerpt. Otherwise there are whole books, or substantial excerpts from all the key works. One of the loveliest achievements of the book is the inclusion of a number of poems of between five and fifteen or so pages in length: not short fragments or sequences, but not very long poems either. This extended length seems to allow Adonis to make, or create, an entirely new poetry. Poems such as ‘Desert’, ‘Candlelight’ and ‘The Child Running Inside Memory’ from The Book of Siege (1985), or ‘Desire Moving through Maps of Matter’ (1987) or ‘In The Embrace of Another Alphabet’ (1994) or ‘Concerto For The Veiled Christ’ and ‘I Imagine A Poet’ (2003) are such. Indeed just to read off the titles of some of these poems gives a sense of the poet’s liberated trajectory. Mattawa also includes a new translation of the single poem ‘This Is My Name’ and the long poem ‘Body’ from Singular In A Plural Form (1975) as well as three of the books of short lyrics published in the first decade of this century and selections from Mihyar and other early books of short sequences. All of this amounts to a considerable selection from the poet’s work, but I’d like to look briefly at two of the slightly longer pieces:

‘Candlelight’ is, simply, a great and extraordinary poem. As with other great poetry, Adonis in this poem sees vision and forward movement as a return, as a circling back, to the early, or to what some would call the primitive. He perceives, has the vision to see, that linear progress, the movement ahead in the direction our eyes show is most vitally achieved by vectoring away in a great circle of human sight. The poem has the appearance and tempo of a prose poem and begins: “Through the years of the civil war, especially during the siege, I learned to create an intimate relationship with darkness, and I began to live in another light that does not come from electricity, or butane, or kerosene. // I despise these last two lamps, they spew a foul odor that kills the sense of smell and poisons the childhood of the air and the air of childhood. They repel the eyes with a beam that pierces vision like a needle. // Moreover they bring petroleum to mind and how it has transformed Arab life into a dark state of confusion and loss. // The other light I love is the light of a candle.”

The memory of candlelight takes him back to his childhood and, by transposition, to the deep temporal roots of culture, to understandings that have been overlain. As he writes: “And don’t you also see that what we call reality is nothing but skin that crumbles as soon as you touch it and begins to reveal what hides under it: that other buried reality where the human being is the poetry of the universe.” Perhaps in this sentence we are at the heart of Adonis’s poetry, the celebration that what is human in being is the poetry of the universe, and the clash therein with the formal logic of the world. He writes elsewhere in this poem:

“This darkness, this secret light, can wrench you even from your shadow and can toss you into a focal point of luminous explosion […] This is when it becomes possible to speak of the light of darkness as it would be possible to speak of the darkness of light.”

The poetry of Adonis can often be a focal point of luminous explosion. Perhaps that is why it has taken so long for his work to cross into the English-speaking world where sentences (and sensitivities) such as “This is how the electricity of life grew inside my limbs” or “to mock that upright stick called the sky” do not sit very comfortably. But Adonis takes us through such luminous explosion “into the warm companionship of the slim candle, to names born under flame”: typically he mentions Gilgamesh, al- Mutannabi, Imru’ ul-Qais, Abu Tammam, Homer, St. John Perse, Heraclitus, Sophocles, Dante, Nietzsche and Rimbaud. And then he ends the poem on this note:

“It is morning: the sun renews its time and life renews its flesh”

‘Concerto For 11th / September / 2001 B.C.’ is both a return to and continuation of the themes Adonis addressed in ‘A Tomb For New York’ from thirty years before, and also a (seismic) meditation on the date 2011, on the destruction of the twin towers in that city and the repercussions on world politics and Arab-American perceptions and relations. It also carries within it latent conversations with the great New York poetry of Whitman and Lorca. But as the title of Adonis’s poem suggests, this poem, while lamenting in anger and empathising with appalling deaths, pinions back to the date 4002 years before and the significance of that time in the world’s history. The time when Gilgamesh “on that night of September 2001 B.C. found the herb that defeats death.”

Here Adonis is questioning what we have allowed to happen across 4000 years that we should have reached where we are. He says: “The present is a slaughterhouse/and civilisation a nuclear inferno” and he is not happy. He says: “And how did a thousand and one nights become a thousand and one armies ?” and he is not happy. And he says, placing these words in brackets: “(Is there anything human in a human being?)” and he is not happy. Twice in the poem he says how tired the earth is and constantly asks when we will put a limit to the despair of this earth. “How can I caution of what’s to come,” he writes “when caution itself is terror?” The whole poem is, as A Time Between Ashes and Roses also was thirty years before, a passionately aimed lament at the aridity of the human intellect, and even of human love. Adonis read this poem at the Poetry International Festival in London in November 2010 and read aloud his poems sparkle and dance with life energies, even when concerned with death. His work is always buried, subsumed and risen out of the physical body of language.

Yet if his poems seem dominated by anger and lament, they aren’t always. For sure anger, lament, rupture and fission elevate his poetry, but so do love, calm, rapture and fusion. In shorter poems he writes:

“The rose leaves its flowerbed

to meet her

The sun is naked

in autumn, nothing except a thread of cloud around her waist

This is how love arrives

in the village where I was born”

This is the opening fragment of the collection ‘Beginnings of the Body, Ends of the Sea’. Mattawa includes the whole collection in Selected Poems and the intensity of Adonis’s love poems is also well represented in the selection translated by Kamal Boullata as If Only The Sea Could Sleep and published by Green Integer in 2003.

One of the great advantages of Khaled Mattawa’s Adonis: Selected Poems is its sheer scale and inclusion. As he says in his translator’s note: “As I read more of Adonis’s work over the years, in the original and in translation, I felt repeatedly that only a large selection of work could give a sense of the myriad stylistic transformations that he had brought to modern poetry at large, through his esthetic renderings of the cultural dilemmas confronting Arab societies in particular.” Following on from the complete translations of Mihyar and A Time Between Ashes and Roses – which give valuable and deep interpretations of those two books – Mattawa’s Selected Poems provides a tremendous overview of the span of Adonis’s poetry and of his oft-repeated but never repetitious vision. That it is published by Yale should ensure its wide dissemination and the quality of both the translations and the book’s production should bring his work close to the reader. Moreover Mattawa is gracious enough to mention previous translators of Adonis, to praise their work and point to their publications (I can think of other great modern poets where this is not the case, where translators want to give the impression theirs is the only source) and this generosity also feeds and widens out our sense of Adonis’s stature.

This stature is serious, visionary. As Samuel Hazo wrote: “There is Arabic poetry before Adonis, and there is Arabic poetry after Adonis.” That is his mark within Arab culture: he ruptured the poetics of the language and he created a new world. And beyond Arab culture, he is a poet of world stature, a poet of rare vision and spirit, a Mediterranean poet who is pan-Mediterranean, one whose work has widened out world poetry and helped make poetry strong in the world. This has nothing to do with power, or with religion, but with the weight, sense and fabric of language, its hidden vortex “where the human being is the poetry of the universe.”

Adonis has always been well served by his French translators, and by Anne Wade Minkowski in particular. The three long poems of A Time Between Ashes and Roses were published as Tombeau pour New York in 1986, almost 20 years before their complete English publication and Mihyar came out with Sindbad in Paris in 1983, 25 years before its US publication. Other substantial books of his poetry and prose appeared in French translation through the 1980s. Moreover consideration of his poetry – both critical and celebratory accounts – have appeared in French over many years. Now, with the appearance of five substantial books in English translation in the decade 2000-2010, culminating with Mattawa’s 400-page Selected Poems, Adonis’s place in English and his place in world poetry in its English reflection are clear and secure. What next for his work? What new prizes and recognitions will he achieve? And, more importantly, where will his language go in the later years of his life and how will his words sound to the people who want to hear him, his readers in Syria and Lebanon, in Damascus and in Beirut and the many elsewheres of the Arab and wider worlds? How will his words reflect on the turmoils and struggles of the various ‘Arab’ springs? And also, on a different note, when will a UK publisher be clear-headed enough to bring out a complete volume of his poetry? We are still waiting for many good and astonishing things and that is something worth saying of a visionary poet who, already past the age of eighty, has said so much and surely still has much more to say.

On translations of Adonis in the UK

by Stephen Watts

The first substantial translations* of Adonis in the UK were published as part of a three-poet anthology from Saqi Books under the title ‘Victims of a Map’ : the other two poets were Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim, the translator was Abdullah al-Udhari and the book was first published in 1984 (with a reprint in 2005). This was my, and many UK readers’, first real introduction to the poetry of Adonis and a first intuition of his poetics. His work, in these translations, made a deep mark on us, not only in long sequences such as ‘The Desert (The Diary of Beirut Under Siege,1982)’, but also in much shorter poems such as ‘A Mirror for The Twentieth Century’ and I think that it’s worth considering al-Udhari’s translation of the latter poem:

A coffin bearing the face of a boy

A book

Written on the belly of a crow

A wild beast hidden in a flower

A rock

Breathing with the lungs of a lunatic

This is it

This is the Twentieth Century

It comes across as a stark and challenging poem: even now, almost twelve years into the following century, the poem has the aura of accuracy and depth. The translation, to my mind and eye, reads very well. It can be compared with Khaled Mattawa’s in the much more recent and extensive ‘Adonis: Selected Poems’:

A Mirror For The Twentieth Century

A coffin that wears the face of a child,

a book

written inside the guts of a crow

a beast trudging forward holding a flower,

a stone

breathing inside the lungs of a madman.

This is it.

This is the twentieth century.

If my memory serves me correctly, Adonis read in London at least twice in the early 1980’s: once in the Kufa Gallery, and once at the then Donmar Warehouse in Covent Garden in a series organised by Michael March parallel with his Keats House readings. But until November 2010, when he read wonderfully with Yang Lian at the Southbank Poetry International, he had not, I think, returned to read here publicly. Perhaps that’s symptomatic: Michael March left London & moved to Prague where he co-ordinates the Prague Writers Festival – he invited Adonis to read there – and Abdullah al-Udhari, who was also invited and read in Prague – moved to Granada some years back, partly at least in disillusion at his own fate as a writer and translator in the UK. There still is no separate volume of Adonis’s poetry published here by a UK publisher, though an early selection is available in above-mentioned Saqi collection ‘Victims of A Map’(reprinted 2005) and in those US titles distributed here, including of course Mattawa’s ‘Selected Poems’ (Yale 2010).

* al-Udhari had published two small chapbooks of Adonis translations in London ‘A Mirror For Autumn’ with Menard Press in 1974 & ‘Mirrors’ with TR Press in 1976.

A brief bibliography of Adonis's works in English translation

Compiled by Stephen Watts

Poetry

The Blood of Adonis, tr. Samuel Hazo & others, Univ. Pittsburgh, 1971.

Transformations of the Lover, tr. Samuel Hazo, Ohio UP, 1983.

Victims of a Map (part only, see pp. 86-165), tr. Abdullah al-Udhari, Saqi, 1984, reprinted 2005.

The Pages of Day & Night, tr. Samuel Hazo, Marlboro Press, 1994 & 2000.

Love Poems: If Only The Sea Could Sleep, tr. Kamal Boullata, Green Integer, 2003.

A Time Between Ashes & Roses, tr. Shawkat M. Toorawa, Syracuse UP, 2004.

Songs of Mihyar the Damascene, tr. Adnan Haydar & Michael Beard, BOA Editions, 2008.

Adonis: Selected Poems, tr. Khaled Mattawa, Yale UP, 2010.

NB: other translations exist in various anthologies of modern Arabic poetry

Prose

An Introduction to Arab Poetics, tr. Catherine Cobham, Saqi & University of Texas Press, 1990, Saqi reprint 2003.

Sufism and Surrealism, tr. Judith Cumberbatch, Saqi Books,

2005.

From Banipal 41 - Celebrating Adonis

Back to top