Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

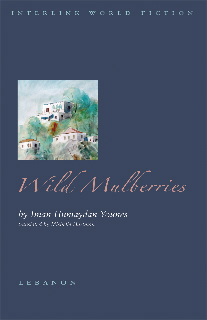

Wild Mulberries

by Iman Humaydan Younes

Translated by Michelle Hartman

Interlink Books, USA, 2008,

pbk, 130pp ISBN: 978-1-56656-700-8

The map and mosaic of Sarah's journey

"October colors the leaves diverse yellows

blended with the damp hues of the earth. The ground becomes wet with silent,

sudden rain, while inside, dryness prevails. Snow does not come to Ayn Tahoon,

nor does the sea. It is a place between the two."

In this place between the sea and the

snows, lonely, meditative teenager Sarah, sitting at a window and contemplating

the changing season, begins to tell, in the first person, the story of

her family; it is here that, at the novel's end, she will return, to

conclude her own long journey of discovery.

Her story, though it begins in the 1930s,

is burdened with past happenings and an ambiguous heritage. Her father is

concerned only with his silkworms (Ayn Tahoon "lives off the silk season"); her

frustrated aunt lives an unfulfilled life on the family estate; her brother -

as Sarah, too, will in her turn - dreams of leaving. In the time between the

wars, old ways are rapidly giving way to the new. The world of the Druze, too,

is not unaffected by this rapid change; the elderly and the conservative within

it cling to their beleaguered past, while the young look for a future in far

away places.

For Sarah, the past is full of unanswered

questions. "Seasons come and go, torn threads reattached by the strength of

nature, the strength of living and survival. My life is reconnected year after

year; and the vestiges of these connections remain recurring riddles, painful

but not fatal. Seasons end and do not return. Nothing returns; I must get used

to that."

Where did the mother who abandoned her go?

Did she find love with a foreign partner, or did she die? Is Sarah who she

thinks she is, her father the Shaykh's daughter, or is she the offspring of a

passing foreigner? To escape from the increasingly oppressive world she

inhabits, Sarah marries her Christian lover. Her travels take her to Southampton, where, she thinks,

answers might await her. But in Iman Humaydan Younus's intricately woven novel,

there are no resolutions or closures, and a journey ends only to begin again.

Sarah's introspective voice, and the deceptively simple manner in which she

tells her tales of longing and loss, at times disguise the novel's ambitions.

She is, in fact, the witness to the passing of a world: the sheltered, insular

world of her Druze family, symbolised by the mulberry trees that fall into neglect

as the old grow older - "hit by illnesses we have never heard of before" - and

the young wander away to more congenial places.

Humaydan is writing primarily for an Arab

audience, and offers few obvious markers along the way: an image here, an

allusion there. Foreign readers are left to find their own way in the maze of

history, but a careful reading of her narrative map reveals the workings of

colonialism and missionary influence, diasporic comings and goings, communal

harmony and sectarian intolerance, social and linguistic change. Sarah's story

ends in a world already engulfed by war, but her introverted, even solipsistic,

musings and the timelessness of the mental and geographical landscape to which

she returns, only make us occasionally and tangentially aware of this.

And yet this is the strength of Humaydan's

very subtle narrative method. In her earlier and very successful novel, B as in

Beirut (Interlink 2008, translated by Max Weiss), she deployed the voices of

four women in one apartment block to present a multi-vocal, almost cinematic

account of the Civil War and its effect

on ordinary lives in the eponymous city.

That very fine novel was distinguished by its juxtaposition of the raw

material of lived experience and a lyrical, passionate manner of telling. Wild

Mulberries is a tauter, quieter performance, devoid of the violence and rage

of the earlier work, and yet, in its

very different way, equally multi-layered, as it introduces the many voices of

Sarah's7 family and neighbours and, through them, the workings of the lost

world they inhabit and that Humaydan so carefully reconstructs in fragments

that, like an archaeologist's discoveries, present a compellingly incomplete

but very immediate and intimate mosaic of that vanished world.

What is most compelling in this novel is

Sarah's poetic sensibility in its evocations of love and letter writing, decay

and growth, exile and motherhood: her world in all its seasons. Rooted in its

regional particularities and yet cosmopolitan, Humaydan's spare style,

sensitively replicated in Michelle Hartman's translation, pays homage to a

number of influences, both Arab and European, though her prose, reflective,

intelligent and pared down to necessities, is ultimately very much her own.

From Banipal 33 - Autumn/Winter 2008

Back to top