Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

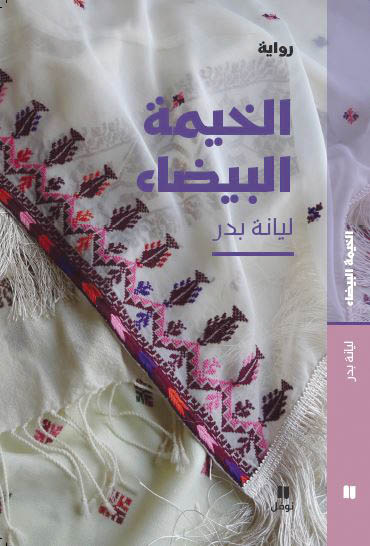

Al-Khaima al-Baidha’

(The White Tent)

by Liana Badr

Published by Hachette Antoine S.A.L.,

Beirut 2016

ISBN: 978-614-438-617-0

In her many works the writer and filmmaker Liana Badr documents the different stages of Palestinian national struggle against occupation and chronicles the Palestinian diaspora experience, including the Nakba of 1948. From her first novel, A Compass for Sunflower, which follows the life of a young woman working in refugee camps in Amman and Beirut, to A Balcony over the Fakihani, three novellas set against the departure from Jordan in 1970 and Israeli airstrikes during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, to Stars of Jericho, set in Jericho pre-1967 war and then revisited post the first Gulf War, to The Eye of the Mirror, which I commissioned as part of the Arab Women Writers Series, her narrative, as Therese Saliba wrote, is : “suffused by nationalist consciousness and critical of masculinist conceptions of nationalism”.

In my introduction in The Eye of the Mirror, I wrote: “The novel is not merely historical or documentary. It transcends what took place to create a mosaic of eye-witness accounts, documents and fictitious testimonies. Liana Badr tries to place Tel-al-Zaatar at the heart of Palestinian consecutive tragedies.” This applies to her latest novel, The White Tent, though her writing has matured and reached new heights.

The novel, which can be considered an ode to Palestine, is set in Ramallah, where the main character, Nashid, lives. Being a filmmaker Badr writes as if she is holding a camera to Ramallah today, and its landmarks: al-Manara Square, the Clock Tower and Water roundabouts, the so-called “Alhambra Palace”, streets, shops and people, and that dark cloud that hangs above it: the Israeli settler colonial state, which manifests itself in the fortified settlements and the tanks surrounding a city constantly under siege. But other towns and cities like Nablus, Jerusalem, Acre, Jaffa and Gaza are also described and their history recounted to commit them to collective memory and assert Palestinian ownership over them.

Like Virginia Woolf in Mrs Dalloway and Michael Cunningham in The Hours, Badr places the action within a single day. The narrative moves swiftly and seamlessly between the external environment, and inside heads of characters. The interior monologue used is punctuated by flashbacks, vignettes and sub stories. Badr layers the voices within the narrative discourse, which allows her to present a rich diversity of Palestinian voices and ideologies and to collect them into a resounding political and social protests against a merciless occupier and a misogynist society.

The first narrative line is from Nashid’s perspective. She is an activist and an observer who constantly documents her life and that of others and her surroundings and ponders the significance of events unfolding quickly. In the twenty-four hours of this novel the reader is offered a glimpse of Nashid’s life, her work at an NGO, her struggle against occupation, and her fear for her son and other youths in a volatile environment where civilians are targeted by the Israeli army and/or collaborators. She is on a mission to save Hajar, who is unmarried, from a possible honour crime.

The second narrative line is from the point of view of the about-to-retire “fidayee, fighter, journalist, revolutionary” Asi, who after fighting for years has becomes a pariah because of his constant criticism of his organisation and its leadership. He feels lonely and unappreciated by a society corrupted by a prolonged occupation. In a divided community and amidst the rise of a new class of mercenaries who are after instant profit at any price: selling their land, building skyscrapers, or exporting Palestinian labour to Israel, he feels alienated. This new class of profiteers has no allegiance or any respect for the past: the long national struggle, the first and second Intifadas, and the war of attrition launched on a daily basis against Palestinians.

His wife, Lamis, whom he had abandoned years before when the national struggle took him from one country to another, has decided to lead her own life. Unlike most, she has a Jerusalem ID and uses it to visit her mother and take care of their old house. She shows remarkable endurance as she crosses the many permanent road blocks and checkpoints maned by the Israeli Military or Border Police every day to assert her right to her Jerusalemite house, which was built hundreds of years ago and was handed down from one generation to another. “Asi imagines her watering the plant pots, clipping the plumosa fern, so it won’t wind itself around the window’s metal grill, obstructing the magnificent view of the Dome of the Rock, tops of houses and vaults of historical churches . . . She takes care of her mother and prepares her food as settlers, who had become compulsory neighbours, throw water and garbage at them.” (page 64)

His wife, Lamis, whom he had abandoned years before when the national struggle took him from one country to another, has decided to lead her own life. Unlike most, she has a Jerusalem ID and uses it to visit her mother and take care of their old house. She shows remarkable endurance as she crosses the many permanent road blocks and checkpoints maned by the Israeli Military or Border Police every day to assert her right to her Jerusalemite house, which was built hundreds of years ago and was handed down from one generation to another. “Asi imagines her watering the plant pots, clipping the plumosa fern, so it won’t wind itself around the window’s metal grill, obstructing the magnificent view of the Dome of the Rock, tops of houses and vaults of historical churches . . . She takes care of her mother and prepares her food as settlers, who had become compulsory neighbours, throw water and garbage at them.” (page 64)

Like Lamis, Nashid has to cross a checkpoint to arrive in Jerusalem and with the help of other women save Hajar from imminent death. In a vivid scene, one you would rarely see in the western media’s coverage of Palestine, Badr describes the despair and impotence of Palestinians degraded, humiliated and abused at the barrier. “The mere thought of crossing that checkpoint fills her with dread and she shudders. She will stand in the queue again in that checkpoint’s corridor made of wrought iron, her body, damp with the sweat of annoyance and hidden fear, shoulder to shoulder with others, as the occupier raises his rifle against them for no reason and without any justification. That hellish barrier there.” (page 72)

The novel also shows what has become of Palestinians after years of arbitrary arrests, deportations and the Israeli West Bank Wall, which divides farming communities and strangles towns and villages. Due to poverty and a lack of job opportunity or economic prospects, many ended up as construction workers and garbage collectors in the prosperous neighbouring settlements. Slowly corruption spreads and entrenches itself in a society constantly under siege. Love and its symbols, like “red roses”, becomes irrelevant in an environment where the individual has no control over his/her surroundings.

The novel is polyphonous and the two main narratives lines are dotted with vignettes about life under occupation. For example, the description of Sit Jawaher’s mysterious death exposes how colonialism and patriarchy are intertwined and sometimes in collusion with each other. Sit Jawaher allows into her house a relative, who attacks her, ties her to the bedframe, and subjects her to a violent interrogation. She subsequently dies of a heart attack. Nashid wonders whether the assailant was after the deeds of her family’s large plot of land and wanted to force her to transfer ownership to her male relatives. Was he a secret agent sent to steal the deeds because the settlement next to their land has its sights on it and wanted to forge the documents to conceal the fact from any future enquiries that it had acquired by force? Or in this patriarchal culture could it be a male relative bent on cleansing his honour?

The Palestinian issue is central to this narrative, but equally so is the “other issue”, namely that of women’s position in society and their bid for freedom. In the past the leadership has prioritised the national struggle over gender equality, but for Badr the two liberations go hand in hand. Throughout the novel, which can easily be classified as feminist literature, there is an attempt to explore, bring to the foreground and validate women’s experiences and subculture. The presence of women in this novel is strong: Nashid, Lamis, Bisan, Nada, Hajar, Sit Jawaher and other unnamed characters, such as Nashid’s mother, are all active members of the Palestinian resistance, but each in her own way. The young have found new ways of fighting occupation using social networks and other means of communication. Bisan, for example, sees the way out through rap music.

The writing sometimes rises from prose to poetic fiction. There are many examples of that and here is my translation of two such sections: “He went to Acre, whose famous walls protected the city from Napoleon and his army. He listened to the gentle hissing of waves as they flirted with the beach, and the quivering and shudders of the silver foam. The children, who leapt into the water and turned into fish twisting this way and that, gleamed like gold.” (page 157) And the following is a description of Palestinian embroidery and its symbols, which can be traced to consecutive civilizations: “The embroidery represents light, that of Venus in its zenith, of the pulsating sun, of the splendid moon in the middle of an indigo sky. You will find the cross stitch which the crusaders brought with them from Europe’s monasteries . . . As for the small keys in the middle of the pine and acacia gardens, it either appeared or disappeared depending on the region where the dress was embroidered.” (page 160)

The two narrative lines are in parallel with each other and here lies a weakness or a missed opportunity. If the two main characters had met, exchanged views on issues raised in the novel, or even contemplated being together, this would have provided tension and an opportunity with both protagonists for transformation or transcendence. It probably would have been difficult to achieve within the constraints of the twenty-four-hour timescale, but a crisis or a challenge could have forced the characters to question their choices and would have enriched the novel.

In his collected of essays The Small Voices of History Ranajit Guha urges us to attend to the small voices of history and stresses the power they may have in challenging the master narrative, “interrupting the telling in the dominate version, breaking up its storyline and making a mess of its plot.” The White Tent does exactly that and is a triumph against acts of erasure of Palestinian history, geography and culture.

Published in Banipal 58 – Arab Literary Awards (Spring 2017)

Reviewed by Fadia Faqir

Click on link for Banipal 58 – Arab Literary Awards contents webpage

To check out Digital Banipal click here