Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

Waciny Laredj reviews

Waciny Laredj reviews

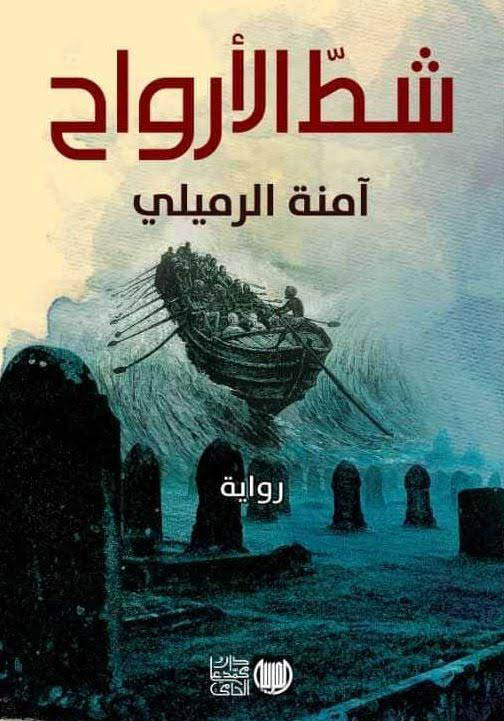

Med Ali Éditions, Sfax, Tunisia, 2020

Beach of Souls by Emna Rmili was published in 2020, by Med Ali Éditions, Tunis (271 pages). The vast critical debate stirred up by its publication quickly made it one of the most important novels published in 2020. Although the theme of illegal migration is not new, Emna Rmili is able—through her exemplary characters—to bring us closer to that unfathomable and also absurd suffering. Stories of people who come with unlimited dreams yet return to their countries in coffins, or as mere news, having been swallowed up by the deadly sea or thrown by the waves, nameless, onto the shore. The lost paradise changes suddenly into a burning hell. The bodies of the dead are not neutral: they carry their own secrets. All the characters in the novel exist within a senselessness in which human lives and tragedies mean nothing at all. How can a country like Nigeria, which is swimming in a sea of oil and gas, allow her children to be homeless? How did Syria get to this situation? It’s not enough for people to tattoo their homelands on their arms, like the young Libyan men did, in order to escape from the eternal hunger of the sea.

But what makes for the quality of this novel is not the tragic theme—sure to shake any reader—but the way the novelist has formed a living matter out of it. It touches us artistically before we are touched by its content, through a genre that is closer to an investigative novel. It resembles the noir genre, which doesn’t reveal the facts all at once but rather draws the reader in slowly. The reader is drawn into the whirlpool of the novel, a spider’s web in which the reader must deconstruct its facts in order to understand it.

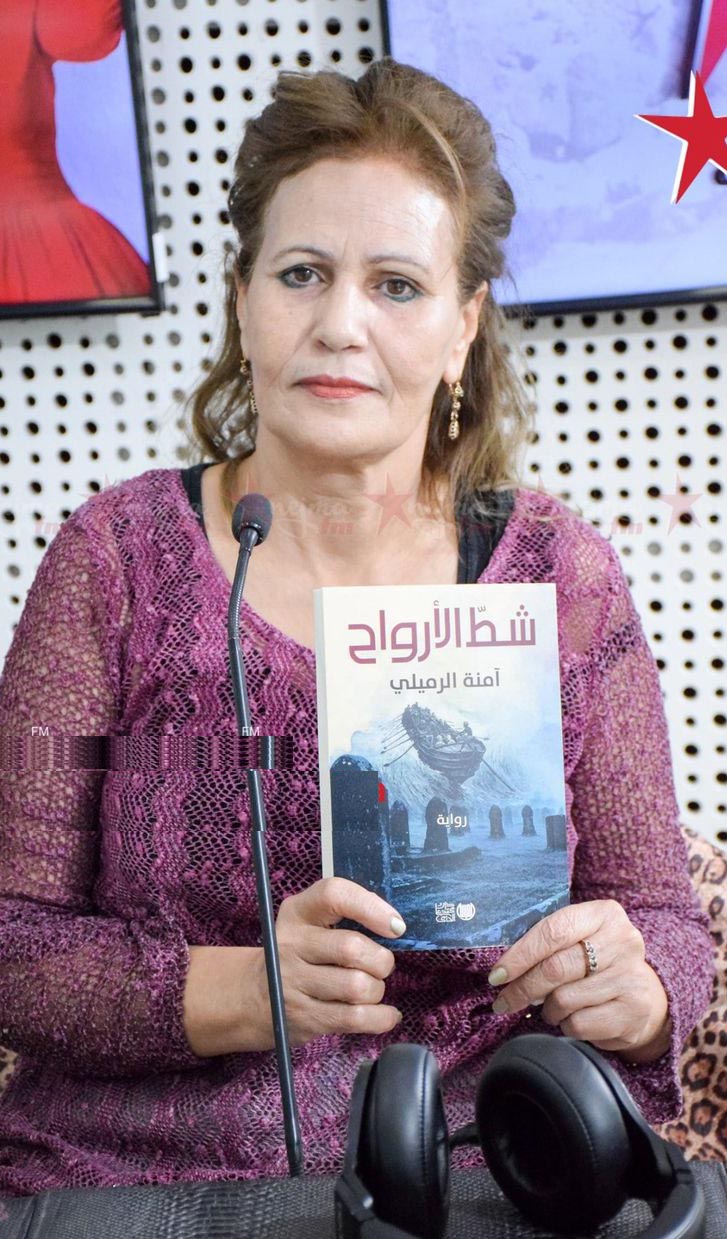

Emna Rmili is an activist, fighting for freedom and rationality, in addition to being an academic. Yet the political aspect that characterises many of her novels does not dominate this one. Rather, she writes with a literary expertise, maintaining the literary quality of the text in its complex artistic structure. Emna Rmili proves to us once again that the novel is hard labor, not something easy and mechanical. The novel as a genre is not only a synonym for life, but also surpasses it, venturing towards the horizons of imagination. It invites a sharp vision and a genuine reading to understand the general societal tools, before transforming them into symbols in the written text. It’s futile to try to find its real-world counterpart, if it ever existed, because the text is bigger than all that. It’s a scream in a world that doesn’t hear anything but what pleases it; it grants a false break for deceived consciences.

Beach of Souls starts with almost a cinematic scene: a physician examining Bahia’s swollen belly. Rather than fear, she enjoys the gel that the doctor put on her body for the ultrasound. It is as if Bahia is rediscovering her body, that her skin is still alive and able to feel what happens to it. Whenever the doctor touches her, Bahia feels a shiver that is closer to pleasure. She asks Bahia about her period, if it has stopped. Bahia answers with a “No, but . . .” “Something, constantly trembling inside me, keeping me from focusing.” (p. 7) “Focusing on writing?” “Did you have a relationship? Do you suspect something?” The answer is also “No, but . . .” Suddenly something appears on the screen which makes the doctor jump: “Good lord, what’s this? What’s this, Bahia?” (p. 9). Bahia floats away, as if only concerned with sensual pleasure. The camera pans out to that mysterious night when Bahia is enjoying her pleasurable repose. The waves, the moon, the frenzy of desire . . . She remembers in disbelief what happened between her and Khaireddine el-Mensi (“the Pasha”) that night. The Pasha buries the dead of the sea. He sells the news of the dead to Bahia, a journalist for an online newspaper; he calls her the “hyena” because she lives off the corpses of the sea’s victims. She writes about them and gets paid for it, so she is sad when the sea doesn’t eject a corpse and she doesn’t have anything to write about. Because of her desire to investigate the truth, Bahia visits her friend, the Pasha, in the Cemetery of the Unknown. He manages the cemetery, right next to the Blue Beast, the center for illegal migrants, which hosts migrants (men and women) from Tunisia, Libya, Syria, Sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere. The Cemetery of the Unknown has no hierarchy, unlike normal cemeteries with their distinctions from the marble tombs down to black cement ones.

Beach of Souls starts with almost a cinematic scene: a physician examining Bahia’s swollen belly. Rather than fear, she enjoys the gel that the doctor put on her body for the ultrasound. It is as if Bahia is rediscovering her body, that her skin is still alive and able to feel what happens to it. Whenever the doctor touches her, Bahia feels a shiver that is closer to pleasure. She asks Bahia about her period, if it has stopped. Bahia answers with a “No, but . . .” “Something, constantly trembling inside me, keeping me from focusing.” (p. 7) “Focusing on writing?” “Did you have a relationship? Do you suspect something?” The answer is also “No, but . . .” Suddenly something appears on the screen which makes the doctor jump: “Good lord, what’s this? What’s this, Bahia?” (p. 9). Bahia floats away, as if only concerned with sensual pleasure. The camera pans out to that mysterious night when Bahia is enjoying her pleasurable repose. The waves, the moon, the frenzy of desire . . . She remembers in disbelief what happened between her and Khaireddine el-Mensi (“the Pasha”) that night. The Pasha buries the dead of the sea. He sells the news of the dead to Bahia, a journalist for an online newspaper; he calls her the “hyena” because she lives off the corpses of the sea’s victims. She writes about them and gets paid for it, so she is sad when the sea doesn’t eject a corpse and she doesn’t have anything to write about. Because of her desire to investigate the truth, Bahia visits her friend, the Pasha, in the Cemetery of the Unknown. He manages the cemetery, right next to the Blue Beast, the center for illegal migrants, which hosts migrants (men and women) from Tunisia, Libya, Syria, Sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere. The Cemetery of the Unknown has no hierarchy, unlike normal cemeteries with their distinctions from the marble tombs down to black cement ones.

The story with Khaireddine el-Mensi originally began with the news on the internet that a Tunisian man had built a cemetery for the dead of the sea. While many considered it a charitable work, others considered it a crime, saying that “he was squeezing money out of the bodies of the dead”. She wanted to find out the truth about the young man. She was able to reach out to him thanks to Facebook, and with the tragic sentence “If you could see what I see” and with “I have been waiting for you, Bahia”, she was able to find him… and fall in love with him. Together they witnessed not only the birth of a love story or the story of the Cemetery of the Unknown, but also a boundless human tragedy. It appears that the novel is based on a real person, Chamseddine Marzouk, a sailor in Zarzis. He has dedicated his life to burying the dead that the sea throws up onto the beach every morning, allowing them to have a final resting place. This investigation would lead her to uncover what was hidden, and to a desperate scream against a nation living in lies: “I’m itching to curse at this nation of tents and stakes, of bent backs ready to depart and live abroad, of a people cursed from the beginning of creation” (p. 140).

When the camera lens widens further, the cruel picture becomes clearer. Illegal migration is not an inevitable destiny decreed by God; it has been manufactured by human hands. The death and smuggling network, those with broken teeth, where a harraga’s* body has no value but as a tool to make money by stripping it of everything including its parts. Bahia devotes much of her time to examining the migrants’ files, the stories of those crossing toward the El Dorado of death. She reveals each person’s tragic background, such as the crying voice of Fatoumata saying, “The man with the broken tooth took my child from me, he snatched him from my back, like he was uprooting a little plant” (p. 166). Njoud, who fled from ISIS terrorists—many of them Tunisian—only to find herself in the hands of the killer of the Beach of Souls. Zahra Chouchane, who had black skin but was not from Mars—she was from Zarzis. She also did not escape the Cemetery of the Unknown. She threw herself at the sea to escape the racism she suffered because of her marriage to a white man. Hayet, a Tunisian woman, who was suffering from cancer and took a bet on the shore, dreaming of life on the other side of the sea. The broken-toothed men are not only gangsters and outlaws; since their job is so lucrative, they are members of the state itself. Bahia doesn’t shrink from uncovering what is hidden in Tunisian society and this makes her a target for both gangs and the state mafia, who consider many of her stories to be fabrications against “the state.”

The Beach of Souls seems like a fairytale place located in a void, with its systems and the life of its managers and the movement of people within it. Its victims waited in “al-Barraka”, where there was no life, just sand, the tide and the wait for death/life, bread and olive oil, and a woman afraid of everything. No language but the language of corpses that reveal some of their secrets: the young Tunisian man who had covered his body with useless college degrees, the young woman who hid cocaine in her belt. Bodies missing some of their parts, some others burned. No authority except those with broken teeth.

The novel ends where it began. The doctor, who has just finished examining Bahia and cleaning her uterus, is wondering whether that had been the fruit of the months she spent with Khaireddine el-Mensi. The camera closes in on Bahia running toward her friend as she realized that he had visited her as she dozed, but dizziness overwhelms her.

* harraga – colloquial term for the illegal migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean from Nortrh Africa.

Published in Banipal 73 – Fiction Past and Present (Spring 2022) along with an excerpt from the novel, translated by Karen McNeil and Miled Faiza.

The Arabic original of this article was published in al-Quds al-Arabi newspaper, and is translated and published here with agreement of the author.

Translated by Karen McNeil and Miled Faiza

About Waciny Laredj

Back to Book Reviews