Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

Continuation of the chapter started in Banipal 69, pages 56-73.

Continuation of the chapter started in Banipal 69, pages 56-73.

Nour, Maha, and Samir arrived in Dar Shams on Friday afternoon. Badri welcomed them in, and invited them to sit on the balcony and have a bite. Contrary to habit, Mohammad was being very sweet. “Although I’m a city girl, I must say I wasn’t expecting your village to be this beautiful,” Maha exclaimed as she took in the cobblestoned streets and gardens in every direction.

After breakfast the following morning Nour, all shiny-eyed, brought out her laptop. She had told Maha about Ripley’s photos from his tour in Palestine and now Samir wanted to pore over them. But like Nour he was not able to piece together anything besides the places where the images had been taken, as indicated on the backs of the photos.

“Do you want my two cents?” he asked Nour.

“Yes.”

“You still know nothing about Ripley.”

“What do you mean?”

“His visit to Palestine was most likely not a ‘touristic’ one.”

“Why not?”

“All that love of the Druze must’ve had something behind it . . .”

“Ha, ha! Aptly skeptical . . . Samir, you’re on to something,” Badri said, grinning.

Disconcerted by Samir’s comment and by her father’s seeming validation of it, Nour asked Samir to elaborate further.

“The English came for us first,” he replied.

“I know.”

“Don’t you see how many photos he took of Jewish people. Why would he do that?”

“I don’t know. But here in Dar Shams, everything we know about Ripley is positive. Not every erudite Westerner is a spook!”

“Whether they were all spies, I can’t say. But by and large, they did more harm than good.”

“I disagree. What about their role in spreading education?”

“All right, all right. I’ll grant you that.”

“And, so what if all the photos are of Jewish subjects? How is that relevant?”

“So long as we don’t know why he was taking those photos, this is all speculation.”

“That’s why we need to know what’s in the journal.”

“Agreed. Once you figure it out, let us know what’s up with the photos.”

Nour did not appreciate Samir prejudging Mr Ripley. She thought about the part he had played, alongside his British, French, and American counterparts, in spreading education in Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, and of the significance of their scientific achievements and the unprecedented opportunities they provided to young men and women of all social classes. Had Sarah Smith not laid the foundation stone of the Beirut School for Girls under the Ottomans in 1835? Was she not followed by Frances Irwin, an educator from Virginia who had established a women’s college in 1924 that decades later became the Lebanese American University, which she, Nour, now attended? Had Protestant women from the United States not come to Lebanon to teach accounting, chemistry, and biology, and even Arabic grammar to women? Had they not facilitated the emergence of a pioneering generation of women who benefited from better opportunities and broader horizons?

The following day, Samir rose early to accompany Badri to a nearby hill. No one had any inkling of their plan to go on a morning outing. When they got back, everyone was up and sitting around the breakfast table. Samir and Badri ate their ful with gusto, and the conversation went back and forth between them like a ping-pong ball bouncing between two accomplished players.

In the evening, everyone was getting ready to go and attend a dance performance in Beit el-Din except Mohammad. Giving him a conspiratorial wink, Salwa tried to persuade her son to change his mind, but his rejoinder was sharp. “Going to see people jumping around in front of you is just inane!” Maha commented that it was enough that they lifted one’s spirits. “It’s deathly boring if you ask me!” Mohammad retorted. “What is this tyranny?” Samir interjected, smiling and stepping towards Mohammad. “Must all of us like dance?” he added. Badri smiled, and Mohammad’s darkened face cleared. The following day, when the taxi came to take Samir to the airport, Badri tapped him on the shoulder warmly. “I’m very happy to have met you, young man,” he said.

* * *

A week later, Nour was waiting for Maha to join her at Orme-Gray for dinner, but when she arrived, she looked distraught, her hair dangling down her face and its greasy roots visible.

“They’ve detained my brother,” Maha said, choking up.

“Whaat!!!”

“They’re accusing him of spying for Hizballah. You’ve no idea what they’ll do to him; you don’t know what the Israelis are capable of!”

“No . . . Unbelievable!”

“The attorney my uncle hired says there is no evidence against him.”

“So, what happened?”

“When he appeared before the judge, she turned out to be Druze!”

“And?”

“The Druze in Israel are pitiless! Far better to have a Jewish judge!”

“Really?”

“They’ve convinced themselves that they had been oppressed until the Israelis came along and liberated them!”

“I don’t quite follow . . . but surely there is hope.”

“Hope? What hope?”

Maha’s eyes welled up with tears and her lips clamped shut as if she were trying to suppress a scream. Nour recovered herself and hugged Maha tightly. “There’s got to be a chink of light somewhere,” she murmured. Feeling Maha’s body shaking in her embrace, she went and got her a glass of cold water. Once Maha had calmed down a little, Nour tried to convince her to stay the night at the dorm, but Maha said she needed to get back to her apartment because she was expecting her mother to call.

Nour felt distraught on account of what had happened to Samir and perplexed by what she had heard about the Israeli Druze judge and the Druze in Israel. She called her parents to talk it over. As if speaking to himself, Badri mumbled: “The Druze in Israel? Well, they serve in the army, don’t they? Nothing much can be expected of them.” Playing the psychologist, Salwa opined that when people were afraid they sheltered behind atavistic impulses, which they then sought to justify. “What we call treason, they consider taqiyya, or rightful dissimulation, deployed in the interest of survival.” Really, taqiyya, thought Nour—that word again, to explain every phenomenon under the sun! “But,” she countered, “hadn’t the Druze of the Golan Heights revolted? Hadn’t they refused Israeli citizenship?” Badri, who was getting irritated by the discussion, put an end to it. “Honey,” he said, “let’s leave this to another time. It’s too complicated to discuss now. The important thing is, why are they charging Samir with helping Hizballah? Do you know anything about his goings and comings when he was here?”

That night, Nour could not sleep. Samir’s eyes were everywhere, those eyes that disappeared into his face every time he laughed. Maha’s rancor and her own parents’ comments about the Druze in Israel kept coming back to her, but things were much murkier now. History, as she had experienced it in Dar Shams, had become a mere possibility, it felt like quicksand loosened from the depths. The pictures in her head no longer reflected reality. Mr Ripley’s journal, a few pages of which she had perused that first time at Nasouh’s home, denigrated the Druze, depicting them as inimical to the Jews, whom they had brutally killed in Safad. And yet today, the Druze were the state of Israel’s most loyal Arab citizens. Everything she had heard seemed so contradictory, just a jumble of loose threads and disparate events.

The next morning, before listening or watching any news she called Maha to check on her. Her friend said she had something important to tell her and suggested they meet in one of the rooms of the Nichols Building at one o’clock. When Nour arrived, Maha was already there, her face more relaxed and her color normal. Maha pulled her hair back and twisted it into a knot. “Listen Nour,” she said, “was your father a follower of George Habash? You know, the PFLP leader?”

“The what? George who?”

“Unbelievable . . . Who hasn’t heard of George Habash?”

“Can you please tell me what this is about?”

“OK, I guess you really don’t know, after all.”

“For God’s sake, spit it out.”

Maha sat back in her chair and closed her eyes. She seemed worn out to Nour’s apprehensive eyes. What did her father have to do with all this? And who was this George that Maha spoke of? The Israelis had been following all Samir’s movements in Lebanon, Maha said. They knew about the trip she and Samir had taken to Sour and to Ras Naqoura, on the border. They had confiscated all his photos––of the hills, of various byways, and even images of the sky—despite the fact that they had been there together with other tourists and some students, and all of them had brought cameras and were taking pictures. When he got back to Shafa ‘Amr, Samir had gone to Ras Naqoura on the Palestinian (Israeli) side of the border, which the Israelis call Rosh HaNikra. And he took more pictures there. The Israelis had immediately detained him and taken him in for questioning. The intelligence officer accused him of taking pictures of Israeli settlements and installations in order to pass them on to Hizballah. Only days earlier, Hizballah had staged an operation against an Israeli military outpost in that very location.

“Sons of bitches! Nothing escapes them,” Maha exclaimed.

“And then what?”

“They asked him point blank why he’d been taking photos there. ‘I was taking photos of my homeland, is that also forbidden?’ he responded . . . They started beating him and tried to . . .” Maha wiped away a tear and continued: “The intelligence officer brought out a large folder full of papers, articles, and photos. He told Samir it was the file of the terrorist, Badri Kamaleddin, an enemy of Israel who belonged to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the PFLP. The officer said that Badri had participated in plane hijackings and the sabotage of petroleum and gas pipelines. Of course, Samir denied knowing anything about this, but they didn’t believe him. They just went on torturing him and interrogating him about the reason for his visit to Dar Shams.”

Nour felt a shudder run through her body like a lightning bolt. She stared at the blackboard spanning the length of the room, and thought about how it framed the view, barring one from reaching outside it, constituting an obstacle beyond which you could not see when standing before it. There was not a single white chalk mark on it, as if it were content with that blackness which had subsumed all the other colors. It appeared like the negative image of objects that do not absorb light in the camera obscura; as if the objects had failed to propagate a copy of themselves that was worth keeping. In that instant, Israel was like the blackboard.

Nour had never heard of the PFLP, or of her father having any kind of political activity. She told Maha that there must be a mistake. Looking her straight in the eye, her friend assured her that the file contained details about her dad, including a photo of him with George Habash.

“All right, but tell me what Hizballah has to do with this,” Nour said.

“The Israelis think that your father is working with Hizballah, and that Samir is of the same view.”

“Who told you all this?”

“An activist from Shafa ‘Amr. He was detained in the same prison as Samir, but as soon as they released him, he came straight to our house and told my uncle (who had come in from Amman) everything that Samir had relayed to him when they were in jail.”

Nour’s mind was brimming with questions, but there were no ready answers it seemed.

She left the university library early in the evening and went wandering through the streets of the city, her face grave as she thought over all the things she had learned about George Habash in one day—how he had been born to a family from Lydda, the city that would swarm with pilgrims from every corner of Palestine coming to visit the Church of St. George in December. Zionist militias had killed hundreds of the city’s residents in 1948 and they threatened those who did not leave voluntarily with a fate similar to that of the villagers of Deir Yassin, despoiling the women of their jewelry after raping them.

* * *

Over the weekend, Badri appeared out of sorts. Nour watched her father as if she were trying to uncover the key to his past life. Feeling drowsy after lunch, she went to her room to take a nap, and woke up around five to the sound of trickling water from the garden fountain, and the cat’s intermittent mewing. She pulled out Alberto Moravia’s The Conformist from her bag to try and finish it—she had only a few pages left. In Marcello’s memory, a series of explosions had taken on a self-annihilating quality, leaving him face to face with his conformity, and the seduction of Fascism and its spiritual rewards. But Nour really could not focus.

Then she finally thought of a way to get herself alone with her father. That evening, she went to the khalwa*. “You’ve blossomed into a lovely young woman, Nour,” said Sitt Muhiba stroking her head. “Is everything OK?” she asked, noticing Nour’s tense features. Nour patted Muhiba’s hand affectionately but said nothing and entered the majlis. She sat on one of the floor cushions by her father and told him everything she had learned from Maha. Badri squirmed uncomfortably and then looked into the distance. She watched as his eyes went back and forth between looking down and then gazing away.

“So, it’s true?” she asked.

“Yes, it’s true. I used to be in the PFLP.”

“Why did you quit?”

“For many reasons. But I continue to respect al-hakim, the doctor. (Nour recalled that George Habash had studied and practiced pediatrics for several years, hence the sobriquet al-hakim.)

Badri went on to tell her about how 1989 had been a watershed. That year, he had shaken himself out of his stagnant state, and it seemed as if he was suddenly looking at his old self in a photo, feeling lonely. Other images arose in his mind, of the Palestinian intifada and children throwing stones. Although the First Intifada was a profound and meaningful event he and his comrades had no part in it. They had dreamt of such an act of popular liberation but had never tried seriously to turn the occupied territories into a theater of confrontation between the Palestinians and Israel. They had not prepared for a long-drawn out conflict that would weaken the occupier’s spirit.

But that wasn’t what had made him pull away from the PFLP, Badri said. His doubts had begun to grow because of the kinds of missions he was being entrusted with. After Habash’s gradual withdrawal from politics, he, Badri, had come to realize that he could no longer support resistance operations that targeted civilians, and especially children, and he didn’t think they were effective or justified anymore. Every time he came home to Dar Shams, his sister Sara would ask: “Is your conscience clear?” and he wasn’t able to answer her. He was also critical of the infamous operation masterminded by the PFLP and executed by members of the Japanese Red Army at Ben-Gurion Airport in 1972, when twenty-six people had been killed. The airport was not a military target, civilians had died, and “the enemy’s foundation remained unshaken”, Badri said, adding that it would have been better for the PFLP to target infrastructural assets like petroleum and gas pipelines.

“I told them I no longer wanted to participate in missions,” he told Nour.

“What missions?”

“I guess you’re no longer a child . . . and I can be candid with you.”

“Tell me.”

“What I’m about to tell you stays strictly between us. It goes to no one, not to Maha, or anyone else. Understood?”

“Yep. Go on, tell me!”

Badri fell silent as though questioning whether to share his secretive past with his daughter. Sitt Muhiba sensed his hesitation, and intervened. “I think it’s wrong to share this with Nour,” she ventured cautiously. “Leave things be. Change the subject!”

“I know how much you fear for her,” he replied calmly, “but I can’t keep deflecting.”

“Be careful, Nour, this isn’t child’s play,” Muhiba said, turning toward the young woman. “Not a word to anyone, no matter who they may be!”

And so it was that Badri embarked on telling his story. He said that he had been entrusted with hiding large sums of money for the PFLP, delivering cash to al-hakim whenever it was needed. The car parked at the bottom of the terraces under the fig tree, the one with the blown-out tires, was the repository for half a million dollars in cash. With that money, the leaders of the PFLP bought weapons and equipment, and more importantly perhaps, information and knowledge. He, Badri, had traveled to Canada and Germany to study airport and airline technologies in preparation for future plane hijackings.

Her Aunt Sara, who had remained silent until now, showed no surprise and did not comment, which meant that she too must have known about this part of her father’s past. Nour’s eyes welled up for a moment. She felt both moved and confused by the revelations. And then a wild idea took hold of her: before her was a fully developed screenplay and really powerful performance, and all that was left for her to do was to direct the film, here in the khalwa, with her father bathed in the harsh glare of the naked electric light bulb against the wall. The film would convey to the audience that although every time he met a young man like Samir he would yearn for the days of the resistance struggle, he went back to his dull life reconciled. The look that had crossed Badri’s eyes merited a close-up of several seconds. And even the raisins in her Aunt Muhiba’s hand, which she had dropped into her mouth, deserved a shot of their own.

The sound of cats meowing in the neighborhood interrupted Nour’s little fantasy. One day, she would be able to understand things. And only then, would she judge her characters, and even so, only on screen. She asked her dad if he had joined any other political party since leaving the PFLP, and he raised his hand high into the air to indicate that he had put a stop to all political activity. “From home to work, and from work to home,” he said. Minutes later, he looked at his watch and exclaimed: “I’m tired, and want to turn in. Yalla, Nour, let’s go.” Before they stepped out, Sitt Sara squeezed Nour’s hand and reminded her that whatever she had heard inside the walls of the khalwa remained there.

As she fell asleep that night, Nour thought about how her father had, in a matter of days, transformed into an entirely different person. She wasn’t sure whether she felt proud of him because he was unique and hadn’t modeled himself on his brothers or because he’d walked away from the party once he’d started to doubt its ethics and the rectitude of what he was doing. Still, she didn’t quite understand how he had managed to distance himself from his past.

Her mind was also on Samir, who was battling both ghosts and victims it seemed to her. The country of which he was a citizen—Israel—wept for the Jew as the eternal victim, the specter that roamed the land, and in this dedication to victimhood, it saw perpetrators everywhere—like someone obsessively taking the same picture of their victim over and over again and convincing others that it was necessary to accumulate more and more Palestinian corpses to heal from their fear.

Despite his lawyer’s best efforts, Samir remained in prison. The tumult that descended on Maha and her mother in the early months of his imprisonment only abated after the interrogations, punctuated with torture, stopped. There was nothing for it but to wait. When Nour remarked to Maha how quickly their wonderful times earlier in the semester had turned into anguish and worry, Maha responded with the adage: “Nothing like November’s luminous moon, and the dark days of December.”

Selected and translated by Maia Tabet from the novel

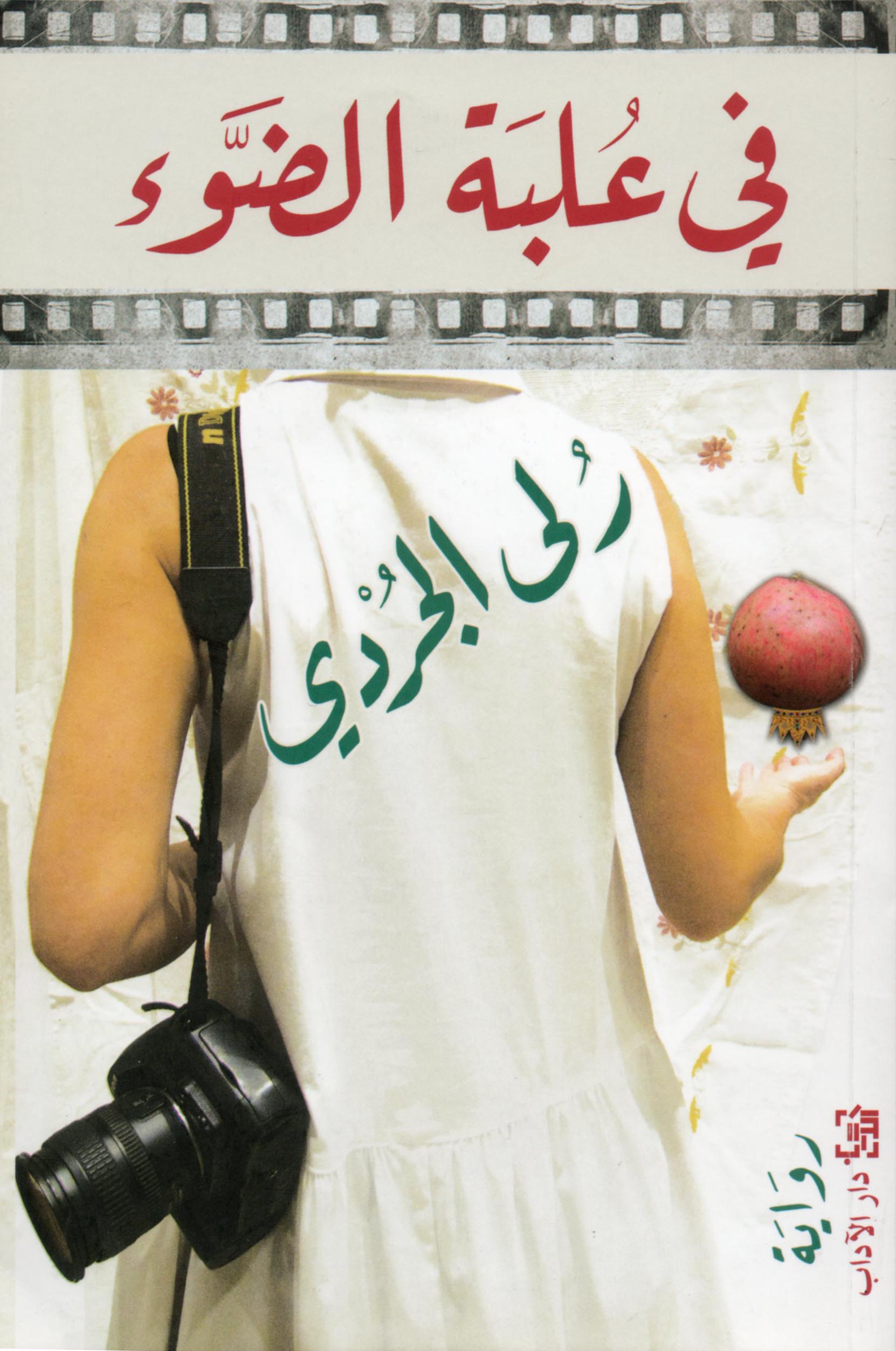

Fi ʿulbat al-dhawʾ (literally "In the Box of Light") by Rula Jurdi

Beirut: Dar al-Adab, 2018. 200 pages.

* the khalwa is the retreat space where Nour’s aunt Sara lives a life of contemplation; the majlis is the sitting-room with seating typically low to the ground.

The first part of this chapter was published in Banipal 69 – 9 New Novels (Autumn/Winter 2020)