Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

Margaret Obank reviews

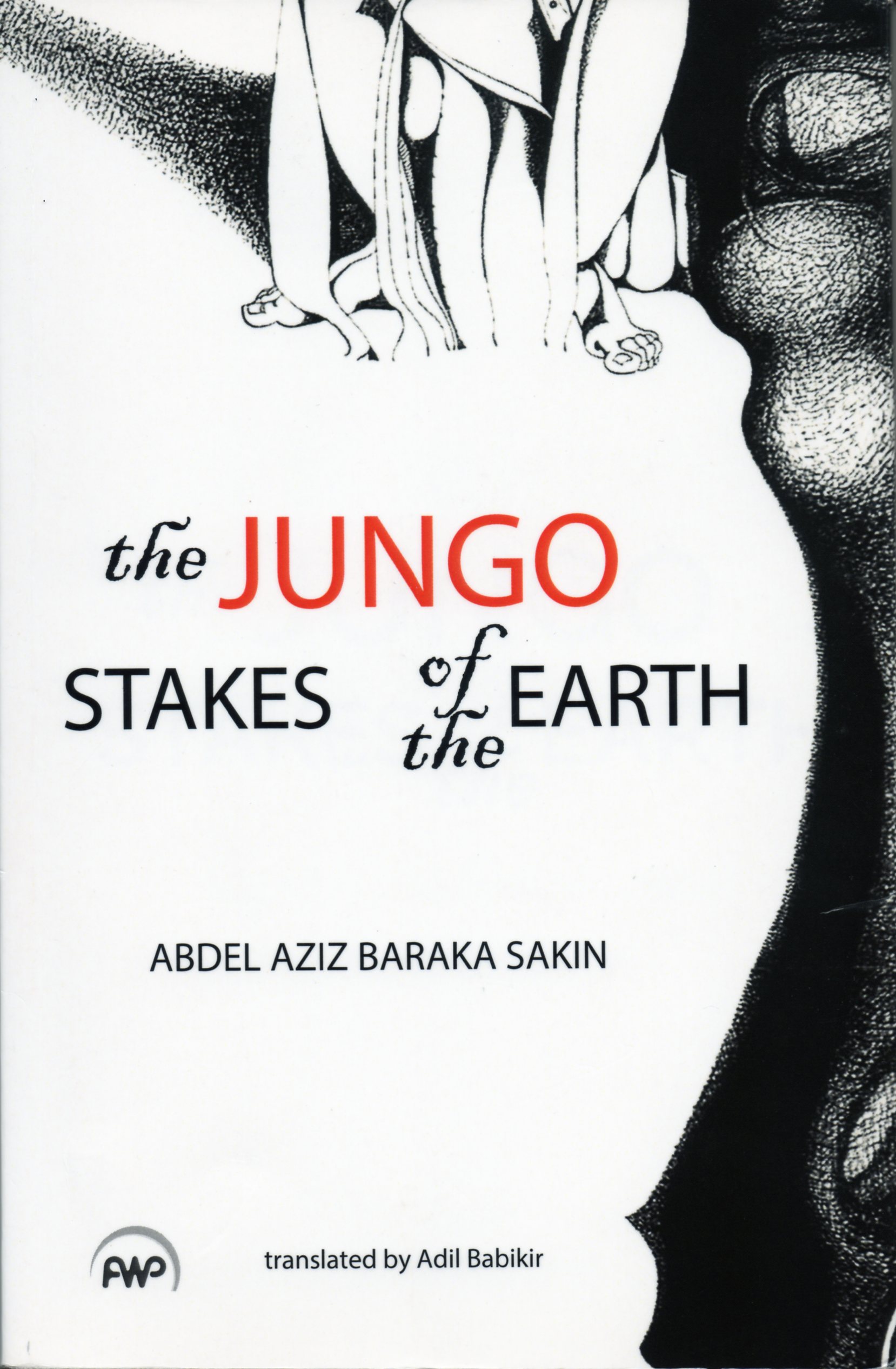

The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth

by Abdel Aziz Baraka Sakin

Translated by Adil Babikir

Published by Africa World Press, Inc, October 2015.

ISBN 9781569024249. Pbk, 242pp, £17.99 / $24.95

A worthy inheritor of Tayeb Salih’s mantle

When The Jungo Stakes of the Earth was published in Arabic in Sudan in 2009 it won the national Tayeb Salih literary prize but in 2010 every copy was confiscated and burned by the Sudanese authorities. This followed an earlier banning of Abdel Aziz Baraka Sakin’s novel Ala Hamish al Arsifa (On the Sidewalks) that was published by Sudan’s own Ministry of Culture in 2005. Fortunately, seven of his eight novels and four short story collections have been reprinted in Egypt. Sakin is one of Sudan’s most widely read and popular authors, mostly now via secret circulation of PDF copies.Adil?Babikir, the translator, has done readers a great service in bringing this outstanding novel into English.

Sakin was forced to leave Sudan after a play adaptation of his novel The Messiah of Darfur (reviewed in Banipal 55), being performed in Sudan by displaced Darfuri children, was used by the government to make propaganda against him.

In the novel under review, which fellow Sudanese author Kamal Elgizouli introduces as “a masterpiece comparable to Tayeb Salib’s Season of Migration to the North”, Sakin has woven a unique story of the two decades of Sudan’s Islamist rulers, since they took power in 1989, through the hard lives, lusty loves and desperate adventures of the marginalised Jungo population of seasonal workers, mainly male, from Western Sudan.

The setting of the novel is the extreme southeast of Sudan, with its inhabitants on the borders with Ethiopia and Eritrea, where the Jungo take whatever agricultural jobs are available through the year, working on sugarcane farms between December and March, clearing shrubs and trees and making charcoal between April and May, and between June and December, in the rainy season and after, planting and harvesting sesame and sorghum. That is, until a “devilish machine” was introduced, impacting on every aspect of life, and the Jungo “felt coldness and bitterness in their souls”.

There is much friendly and open banter between the many different characters in the novel, men and women, while a mix of languages and ethnicities abounds in Sakin’s sympathetic and powerful narrative. Women take their turn making the local mareesa beer and arrack, and are strong, independent individuals. But life for the Jungo is hard and unjust, banks discriminate against them, refusing to lend them money, even after they launch the “shit revolt”. The narrator, often with his friends Wad Ammoona and Mukhtar Ali, gives readers fascinating insights into the complex humanity and tolerance shown by this diverse and marginalised population, as when they listen in on sesame bargaining between the Jungo and Jellaba merchants in a crowded souk.

Collisions with the government begin when desperate Jungo start a revolt and become bandits in their struggle for survival. Government forces hound some over the Ethiopian border and they become refugees, including the nameless narrator and his friends, while other Jungo are said to have been joined by young men from the Lahawyieen and Homran tribes, training in Eritrea, though it is also said that negotiations were going on with the armed rebels for a peace agreement. Through it all, Sakin threads a gentle love story – with a happy and unexpected ending – between the narrator and his Ethiopian girlfriend Alam Gishi, who was introduced to him at first as a one-night stand, but captured his heart.

Published in Banipal 56 – Generation '56