Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

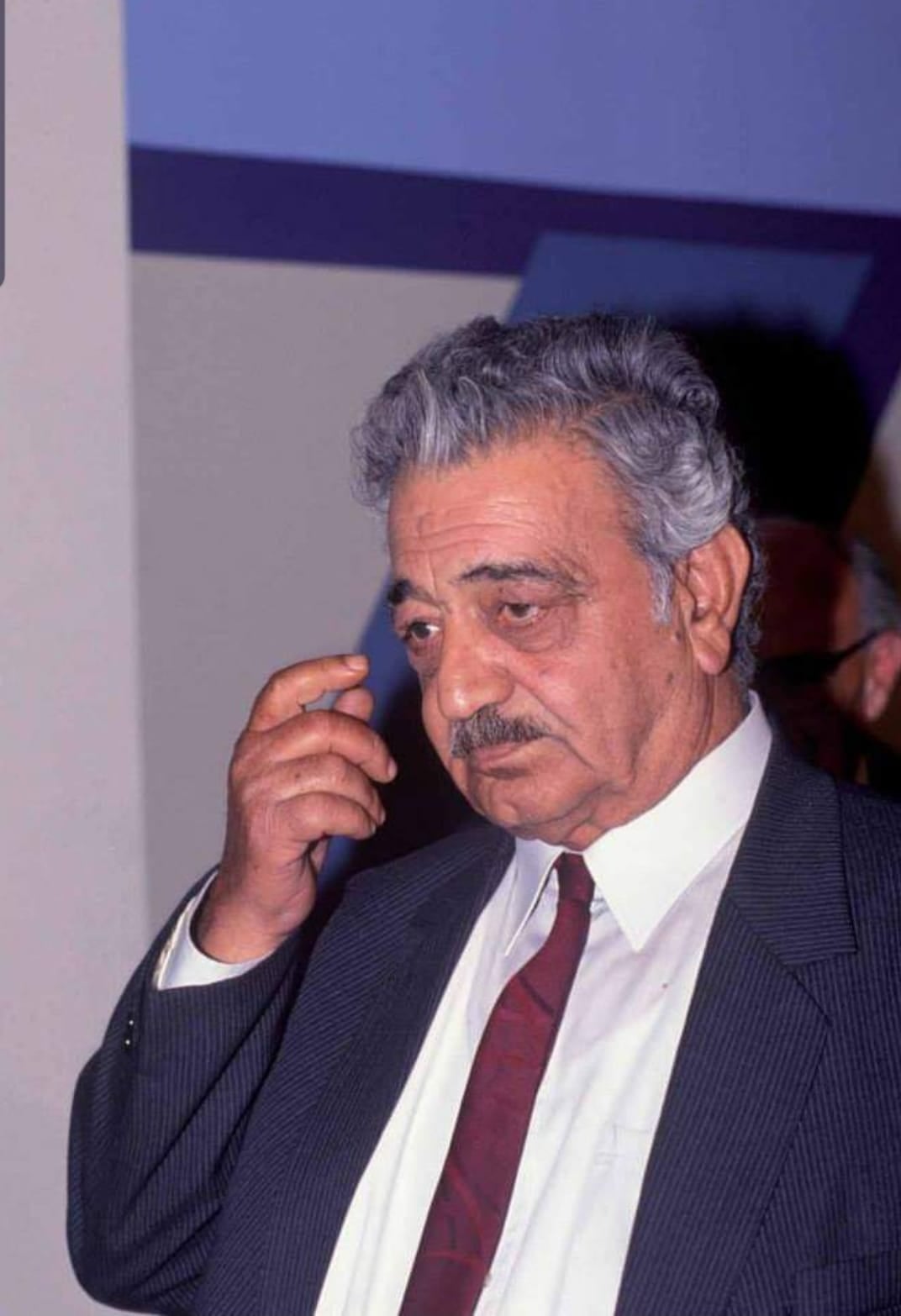

Introduction by Graham LIddell to Emile Habiby’s Sextet of the Six-Day War and two of its stories published in Banipal 73

Plus the 6th story, "The Love in My Heart"

The translations featured here are two stories from Emile Habiby’s Sextet of the Six-Day War, a collection of short fiction set in the aftermath of the 1967 conflict that ended in Israel’s capture of Palestinian, Syrian, and Egyptian territory. This moment in history, known as the Naksa or Setback, reverberated throughout the Arab world as an abject failure of Pan-Arabism, and marked the beginning of Israel’s longest-standing violation of international norms—its military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and refusal to grant political rights to their inhabitants. To this day, the demand to end the occupation remains the single loudest rallying cry for Palestine solidarity activists worldwide. And yet, while Habiby dwells with great sensitivity on the weight of this catastrophe (for what was the Naksa if not another iteration of the 1948 Nakba?), he can’t help but zero in on a twist of fate that it brought about: Palestinian families and friends who had been divided from one another, living in separate territories ruled by bitter foes, were now gathered together under a single regime, and could visit one another for the first time in almost two decades.

Explaining the collection’s title, Habiby writes:

If they’d called it “The Seven-Day War” I would have composed it as a septet, in order to flip the name on its head so that we, and they, could see the other side of the tragedy of this war: someone who has been imprisoned and separated from his family for 20 years wakes up one morning to a clamor in the prison yard, and all of a sudden his entire family is thrown in and crammed together with him. How should he feel about this reunion, or any reunion, after all this time being cut off and isolated?

How can one even think of rejoicing at such a time of mourning and misery? This transgressive positivity, this tragicomic “pessoptimism,” is one of Habiby’s most distinguishing authorial traits. It is introduced to the reader quite innocently in the character of Mas‘oud, the rambunctious ten-year-old boy who is the first story’s titular subject. The 1967 Arab defeat is, ironically, the cause of Mas‘oud’s world being turned right side up. Teased all his life for his lack of family connections in a Palestinian village in Israel that is made up mostly of people who are each other’s relatives, he is surprised to learn that he has a cousin who has come to visit from the West Bank. Suddenly, Mas‘oud feels respected and included among his peers. Though adamant that the Israelis “must withdraw” from the West Bank, he can’t shake his fear that upon their withdrawal he will revert to his former status as “cut off from root and branch”. Of course, he verbalizes this worry to no one—except, perhaps, to the “little bird” who then recounts it to the narrator.

How can one even think of rejoicing at such a time of mourning and misery? This transgressive positivity, this tragicomic “pessoptimism,” is one of Habiby’s most distinguishing authorial traits. It is introduced to the reader quite innocently in the character of Mas‘oud, the rambunctious ten-year-old boy who is the first story’s titular subject. The 1967 Arab defeat is, ironically, the cause of Mas‘oud’s world being turned right side up. Teased all his life for his lack of family connections in a Palestinian village in Israel that is made up mostly of people who are each other’s relatives, he is surprised to learn that he has a cousin who has come to visit from the West Bank. Suddenly, Mas‘oud feels respected and included among his peers. Though adamant that the Israelis “must withdraw” from the West Bank, he can’t shake his fear that upon their withdrawal he will revert to his former status as “cut off from root and branch”. Of course, he verbalizes this worry to no one—except, perhaps, to the “little bird” who then recounts it to the narrator.

The collection’s final story, translated here as “The Love in My Heart”, takes on a much more serious tone, and poses a timely question: how is international solidarity, or even solidarity between Palestinians living in different places and circumstances, truly possible given that various groups’ experiences of trauma differ so vastly in scale? Habiby’s narrator finds himself at a loss after he pledges to write about the horrors of the siege of Leningrad in World War II, while visiting the city and attending a mourning ceremony. The best he can do is tell the all-but-unrelated story of two young Palestinian women, one from the West Bank and the other from Israel, who are imprisoned together after being accused of aiding terrorists. Here, the former wonders for the first time if perhaps the tragedy of Palestinians who remained in what became Israel was even greater than the tragedy of those like her parents who fled as refugees to the West Bank. The latter woman, separated from her home for the first time but newly connected to her estranged compatriots in prison, somehow experiences this displacement as finally having arrived in her homeland.

Habiby died 26 years ago this May, forever “remaining in Haifa”, his hometown. He didn’t live to see the Second Intifada, nor Israel’s perennial destruction of vast swathes of the Gaza Strip, nor the ongoing dispossession campaigns in East Jerusalem. If he had, would he have managed to retain his mischievously hopeful spirit, the one that drove him—in the face of intense criticism from all sides—to accept literary prizes from both the PLO and the Israeli state? Or would a more practical pessimism finally have won out?

* The translator wishes to thank Siham Daoud, who cofounded Arabesque Publishing House with Habiby in 1989, for her approval of this project.

* * *

Story VI

Story VI

May the anguish that engulfed you

be soon followed by reprieve

And may the fearful find safety, the captive be ransomed,

and the faraway stranger come home to his relief

(A song Fairuz did not sing)

A song Fairuz did not sing in words, but she does sing it in warmth.

And neither was I the author of the story that you are looking at right now. But I rewrote the text once, I rewrote the text twice, and three times, in order to hide the story’s identifying features from its true protagonists, so as not to distress them – but then I became distressed – and in order to hide its identifying features from their jailers, so as not to provoke them – but then I become provoked.

If it weren’t for my fear of being betrayed by age, I would have preferred to keep the story folded away in notebooks until the situation changed, and then release it without any of the kohl of fiction adorning its eyelids.

And if it weren’t for my fear, also, that the situation will continue dragging on the way it is for a long time . . .

How difficult it is for fiction to be born in a living story!

Flashes of pain abound in the author’s chest for nine months, nine years, his whole life, until the contractions rattle him and a story is born. And if it can breathe the air of our world, it lives. But if, on the other hand, it has fallen down to us from another planet where they don’t breathe the same air as ours, it suffocates, and it is stillborn.

And even more difficult than that is the birth of truth in a story that is bundled up in fiction to shield it from the bite of the cold.

Like a flash of lightning, you can’t hold it inside your chest for a month – you can’t hold it even for a moment. Either it rips open the veil of darkness and you see what is in front of you, and you cry out, “Now I can see what it is that’s in front of me!” or it rips your guts to shreds, and you can’t see what is in front of you anymore, and you let out a moan.

When I was in Leningrad this summer, the city’s clear sky split open with a flash of lighting.

The day was cloudless, and the morning was glittering with the sun’s rays. Our eyes, however, were overcast when we entered the vast square that was blooming with roses and poppies, fragrant with the scent of myrtle, carnations, and forget-me-nots. The square held the graves of more than 600,000 Leningraders who died, mostly from starvation, during the 900-day siege of Leningrad in World War II, which lasted from September 1941 until February 1944.

Standing before us in the heart of the square, one kilometer away from its entrance, was a colossal, dark granite statue of a woman partially wrapped in a gown, arms outstretched in grief – the statue of the homeland’s suffering.

We passed between the radiant graves: large flower pots planted with aromatic myrtle, every grave containing thousands of victims who died, month by month, year by year. The solemn music filled the emptiness around us and in our hearts.

Coming from the depths of the profound, mournful melody, thousands of people began to gather in this place, slowly and deliberately. Men and women and children, young ladies and old folks, soldiers and little kids, scattering bunches of flowers on these bunches of graves, standing in front of the flowerpots and watering them with tears. We noticed an old woman holding onto a little girl’s hand. The child was rushing ahead and pulling her sluggish grandmother behind her. The little girl was carrying a bouquet of red hyacinths. She would stand in front of a group of graves and toss a hyacinth onto them, then drag her grandmother toward another group of graves and toss a hyacinth onto those ones. And the grandmother would follow slowly, laboriously, behind her. With her closed hand, the grandmother would wipe a tear from this eye and a tear from that eye. Perhaps one of these red hyacinths could serve as a boutonnière on what remained of the jacket that she had shrouded her husband with five-and-twenty years ago, and he would beam smilingly at her, and she would choke up.

We put black sunglasses over our eyes, for fear that the Leningraders would notice that we were infringing upon something in which we had no share. We were holding lit cigarettes, so we put them out in our hands before dropping what remained of them in our pockets, for how despicable it would be for pockets to burn while hearts are burning!

And when we approached the statue of the homeland’s suffering, lines of poetry engraved on the base of the statue were translated for us:

“Here lie thousands . . .

“Of men and women and soldiers and children . . .

“The granite immortalizes them . . .

“But know this . . .

“We will not forget a single one of them . . .

“Ever . . .”

Granite is dead – there is no life in it. And dead, likewise, is this description of mine – there is no life in it. I don’t know if it’s possible to take a photograph of lightning. And even if that were possible, the picture wouldn’t truly capture its flash. Haven’t you noticed that when lightning flashes before your eyes, you pay more attention to what it reveals of what the darkness had been concealing than you do to the sight of the lightning itself?

And yet, we saw a photograph of lightning.

Beside the graveyard square, to the right of its entrance, stood a modest building with a collection of artifacts that once belonged to the victims, proof of their existence and of what they suffered.

And when we entered this modest building, two eyes gazed into ours: the eyes of a child in tattered rags, with an emaciated body, like a forgotten fig tree in one of our country’s stolen fields. He was five or six years old, on a main street, amidst ruins and rubble and smoke and death, in a large photograph. His eyes were shriveled in bewilderment. What is this? Why? Where do I go?

His eyes alone were open. Everything else of his was sealed, from his mouth to his scrawny fists.

Scarcely had this boy begun to blossom under the care of his mother, and scarcely had he learned that if he called for her she would caress his aches with the tenderness of her palms when this thing came: the thing whose name he didn’t know was war. It locked up his mouth and muted his calls for his mother, his cruel mother, who refused to listen, who refused to respond. And in his chest, the question his mouth kept locked away: Mom, why don’t you answer?

My wife rushed out of the building, sobbing. So I went after her.

“What is it?”

“Doesn’t he look like our son?”

“No, no, these people don’t resemble anyone. Nobody has endured what they’ve endured. And what they are still enduring. And what we still ask them to endure.”

But our Leningrader companions called for us to come back. They said we couldn’t leave without seeing the journal.

What journal?

We went back inside the modest building and saw the journal that was kept underneath a glass cover so that it would be preserved.

This is the journal of a Leningrader girl who was seven years old when she wrote about the siege of Leningrad. The name of this girl is Tanya Savicheva.

She kept her diary, writing in a worn school notebook.

Writing?

You can imagine what a child of seven is able to scribble with her pen.

On one page of the notebook, three or four words, slanting downwards, letters crooked. This way the pages are filled up.

Our companions translated for us what was said in these pages. I didn’t have the heart to transcribe what they translated. There was a sense of awe for the place, and a trembling in my hand. But the diary entries proceeded in something like the following manner:

“Today my grandmother died.”

“My little brother didn’t wake up in the morning.”

“Today they carried my little friend away on a sled.”

“I learned today that the neighbor lady died.”

“Today they took my sleeping mother away and she didn’t come back.”

And the last line of the journal’s last page:

“Today I am the only one left.”

They found this journal among the rubble. And they told us that they found its owner, the child Tanya. They tried to save her from starvation, but she didn’t live much longer after that.

I didn’t become conscious of myself again until after I told them: “I will write about what I witnessed.”

But that night, the pangs of regret kept me from sleeping. Write? Mashallah. What, do I think I’m doing them a favor? And is this pen that was sharpened by the granite of journalistic writing, and whose horizons have been narrowed by the incarcerations of everyday life, capable of translating what was snuffed out of the two bewildered eyes, and what flashed forth in the damning lines of the journal?

Until I happened upon the letters of a Jerusalemite girl, a young woman eighteen years of age, held captive in Ramla prison. A kind of diary, or journal, that she dispatched to her mother when nobody was looking.

When nobody was looking, she would write her letters on the papers of Degel cigarettes, which were permitted to be sent to prisoners, who were allotted four cigarettes per day. And don’t expect any further details from me.

Here, imagination intermingles with reality until you can’t separate fact from fiction. Just as after we’ve become advanced in age, we can no longer distinguish between what happened to us in our youth and what, at that time, we were dreaming might happen.

One must suppose that the recent incident of the three Jerusalemite girls, who were arrested on the accusation of smuggling weapons or covering up the smuggling of weapons, and the frenzy that raged in the press and in public opinion regarding their arrest and torture, and what was published about them being crammed in together with prostitutes, and about cigarettes being put out on their soft bodies and other humiliations and attempts to take away their dignity, and what I can imagine, and what I already know, about the conditions of the prisons, and about the hunger of the imprisoned for freedom and human dignity and security and friends and food and sun and compassion, and the concern of the imprisoned about the concern of his family for him, and his fear of them worrying – one must suppose that this is what brought to mind the thought of these letters, this diary, this journal.

Let us give the young woman, the author of the letters, the name Fairuz. And let us change the names of her loved ones who are mentioned in her letters.

Why have we chosen this name for her and not the name “Tanya”, for example?

Because Tanya was younger than her in age. And because we believe she will live much longer after this. And because Tanya, given what she went through, is older and greater than her.

We have chosen the name Fairuz because that name moves us, by the tranquility of its sound and the dandling lullabies contained within it, like the effect a mother has on her child when she cradles his achy head and begins to caress his brow ever so gently, ever so lightly, until his headache ebbs away.

I will not inform you of everything that is in these letters, but rather will choose what I please from their contents, whatever resonates painfully with me and with you, until God’s will be done.

The First Letter

Beloved Mama,

My most pleasant wishes and sweetest prayers to you and the whole family.

We will meet again in wellness and joy and relief and new sunshine.

Please, dear one, watch over your health and calm your nerves. We’ve grown up and must now manage our problems on our own.

May the Lord trade your weariness on our behalf for wellness and happiness, because you have carried our burden for far too long. And today the time has come for us to manage our own joys and sorrows. I’m making you swear by God to calm your soul and your nerves, and to pray for us without any anxiety.

Don’t be concerned for me or for my job. It is guaranteed. Please, family, write to Hasan regularly (this is her fiancé and he is detained as well – E.H.).

And you, my beloved sister, write to Hasan and to your husband, too (her sister’s husband is also detained – E.H.).

Now I am living in a nice room with the rest of the young Arab women, and we enjoy each other’s company. Of course, none of you knows anything. But don’t worry. Please send the following items with anybody who comes, or with the lawyer:

1 Some Arabic and English magazines, from under my bedside table.

2 A hairbrush, plastic flip-flops, Nabulsi soap, and toothpaste.

3 Nightgowns, blouses, and a couple of neat skirts, because we have to look good in front of the Jews.

4 Olive oil in a little can, since glass is prohibited. Everyone who is in charge of us is well-mannered, so don’t worry, Mama.

5 A little watermelon + 2 kilos of lemons + good apples + bananas and peaches + red and green grapes + oranges and cucumbers + pickles from a clean restaurant + olives in a bag.

6 A chicken or two with onions + kebab like the kind my sister brought. I have been missing it very much.

A girl here with me wants a rooster, instead! Hahaha. Please sister, Umm al-Waleed, do not forget anything. All the items are permitted to enter. Don’t let this make you think we are going hungry. Don’t worry. We spend our time telling jokes and pleasant anecdotes.

And I write poetry all the time.

Another friend says how nice the climate of the Ramla prison is, not like the climate of Natanya prison. So don’t worry. By the way, I taught all the Arab girls who are with me to pray, and we’re always praying for the lawyer, who is making a huge effort.

Send me Hasan’s letters so that I can read them. We pray and read the Quran, and I’m always praying for Father’s soul to rest in peace. I also pray for all of you together.

I dedicate this song to you: “Tul ma ’amali ma‘aaya wal-hubb fi qalbi . . . As long as my hope is with me and love is in my heart . . .”

Until very soon,

Your daughter

Beloved Mama,

Praise God that you are in good health. I was overjoyed when the lawyer told me that you will visit me next week and bring us the exquisite foods that I requested. This means that my letter arrived, which means that this letter will arrive as well. May God increase the number of kindhearted people!

My friend tells me that there are angels even in hell. She is my new friend who I want to tell you about, Mama. She is not from around where we live, but from Haifa. Meaning she is an Arab from Israel. And she has been detained since the June war, also without a trial, and on the accusation of communication with the enemy. And this week they moved her to our room, which is called a qawoosh, or a prison cell. So we’ve welcomed her and she’s become one of us, and it’s as if we’ve known each other since childhood.

She is a member of the al-Saari family from Haifa, and they used to live in Wadi al-Saleeb, where your family used to live, Mama. And she says that her mama would no doubt remember you all. And this Haifawi friend is a poet like me – ahem! ahem! – and a jokester too, and we’ve taken to singing together. But, while I love Abd al-Wahhab, she doesn’t like anyone but Fairuz, and especially her song “Raaji‘oon – We Shall Return, We Shall Return”.

We all sit around her and marvel at her ideas. I asked her: “What is it that moves you in the song ‘We Shall Return, We Shall Return’ when you never departed and never returned, but rather stayed in your homeland?”

She replied: “My homeland? I feel like a refugee in a foreign country. You dream of the return and live on that dream. As for me, where would I return to?”

And, my beloved sister Umm al-Waleed, this Haifawi friend adores al-Mutanabbi and his poetry just as you do. And when she talks about her lost paradise, and about her homeland that she lives in but whose presence she does not feel, she repeats the lines of al-Mutanabbi that we learned from her, and we’ve begun to sing them to the tunes of Umm Kulthum’s nationalistic songs:

Among all dwelling places, Shi‘b is the most fragrant

Like spring among the seasons

Playgrounds for jinns, if Solomon passed through

He’d sure need an interpreter

Do you know these lines, Umm al-Waleed?

And this Haifawi friend says that she doesn’t sense her homeland except when she sits next to her mother on the mattress at night before going to sleep, and her mother tells her about the good old days when her six brothers were still in the house. And they would sleep on the floor. And they would laugh and argue. And in the morning, the mother would pack lunches for them. One went to work, and another went to school. And now her six brothers have been scattered to all the corners of the world – in Kuwait, in Saudi Arabia, in Abu Dhabi, in Beirut, and one in the grave.

And she also has two lines of poetry about the separation of her brothers, by an old poet. And here she is writing them in this letter in her own handwriting:

I was once the seventh of seven brothers

If only any of that life lasted, O Dareem!

They took my soul with them when they departed

And life henceforth has been pure gloom and reproach

Is she not more eloquent than you, Umm al-Waleed?

And she always beats us in poetry competitions. But, sometimes, when I am unable to remember a particular line, I compose one on the spot. And she says: “Out of meter! But that’s all right, for the sake of your Haifawi mother!”

We asked her: “Since you live in this country, and you know more than we know, how do you see the future?”

And she replied in anguish: “As soon as I start to think about the future all I can see is the past. What can I tell you? The future that I dream of is the past. Is that possible?”

Now I understand, Mama, why you refuse to visit Haifa. Sweet, caring Mama, aren’t you afraid of feeling what this Haifawi girl feels?

We never knew the feelings of our brothers and sisters who stayed behind . . . or their tragedy . . . is it greater than our tragedy?

By the way, if this letter reaches you before you come to visit us, please cook the chicken as msakhan and not as mhammar, by special request from our Haifawi poet, who says that with us, even in this qawoosh, she now feels that she is in her homeland.

And don’t forget the chocolate and the filled Arab cookies and that good candy made in Nablus, in a plastic bag.

Please send sesame ka‘ak, about six of them, and put them in a plastic bag so they don’t get dry. And make sure the fruit is hard to the touch so it lasts longer, especially the tomatoes, because the food here is so often dry. But don’t worry.

Ask Lamia to prepare me some hilba, and send kisses from me and my Haifawi friend to her.

Please send ten cents’ worth of falafel from Abdu’s + pickles + hot peppers. Send sunflower seeds and a half-kilo of qdaameh, you know, a mixture of roasted chickpeas. And a kilo of burmah sweets, made with pistachios, is urgently needed. We are really missing food and sweets. But please don’t get sad.

Umm al-Waleed, be careful not to forget anything, since Mother has the money. Take from her and buy these things for me. Ask my aunt and uncle to visit Hasan.

My greetings to all the olive-skinned ones. My greetings to sweet little Nuna. And to my dear mother-in-law and father-in-law.

Did I dedicate a song to you in my last letter? No harm in sending it to you again here, even if it is for the second time.

I dedicate this song to you: “As long as my hope is with me and love is in my heart . . .”

This is what I am trying to instill in the heart of my Haifawi friend.

Until very soon,

Your daughter

Beloved Mama,

………………………………………..

………………………………………..

(But you read this letter, just as I did, in the press. It was published during the trial of the Jewish police officer, whom they fired from her job and sentenced to a year of probation, when they found out that she was the one who had been smuggling Fairuz’s letters to her mother. Angels do exist, even in hell!

(Except I am sure that what was published was full of distortions.

(Everything mentioned in the press, as if it were quoted from this letter, concerning Fairuz’s “agreement with the Haifawi girl to form a secret cell inside Israel” is sheer distortion of an innocent friendship. An innocent friendship between two girls from one people, meeting together after a long separation, under one roof, the roof of the prison cell.)

Selected from Sudasiyyat al-Ayyam al-Sitta (Sextet of the Six Days [War]), introduced and translated by Graham Liddell

Published in Banipal 73 – Fiction Past and Present (Spring 2022)

Link to more Selections