Receive Our Newsletter

For news of readings, events and new titles.

Becki Maddock reviews

Becki Maddock reviews

Agadir by Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine

Translated by Pierre Joris

and Jake Syersak

Publisher: Dialogos / Lavender Ink

Pub Date: 20/8/2020

Pbk, Pages 134

ISBN: 978-1-944884-85-7

Agadir is not your average novel. I guarantee you will not read anything else like it this year, or perhaps ever. Sometimes described as a hybrid novel, it is not a novel in any conventional sense. Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s intense writing intentionally subverts traditional literary models. There is no plot or character development in Agadir. The work begins with a two-page paragraph, consisting of a single sentence containing no punctuation but for an initial capital letter and a final full stop. But do not be deterred, it is worth persevering. The punctuation kicks in on the third page. The experimental work incorporates many different styles of writing. There are passages of prose, some with punctuation, some without; there is poetry and there is dialogue, often written in the style of a script for a play, and incorporating many poetic speeches. There is a letter from the narrator’s “future assassin”, a man trying to locate his house, destroyed by the earthquake. Some parts of the text are all in upper case. Some are merely a list of words: “milestones pedestrians motorists cyclists kings chestnuts writers logistics…” But each word is important.

The English edition of Agadir includes a useful introduction by Khalid Lyamlahy, a Moroccan academic whose PhD focused on the work of three contemporary Moroccan writers, including Khaïr-Eddine. The introduction provides some background on the author’s life and work, helpfully setting Agadir in context and explaining some of the characteristics of Khaïr-Eddine’s unique writing style.

Readers who wish to learn more about Khaïr-Eddine’s work would also be well advised to refer to Banipal 10/11 (2001), which contains a special feature on the author, featuring translations of his work and tributes to Khaïr-Eddine from writers who knew him, including Pierre Joris, Jean-Paul Michel and Samuel Shimon.

Poet and writer Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine was one of the most innovative North African writers of his generation. He was born in 1941 in Tafraout in the Anti-Atlas mountains of southern Morocco. He was part of a group of Moroccan poets and artists who founded the avant-garde journal Souffles (Breaths) in 1966. It was banned in 1972. Khaïr-Eddine wrote in French, publishing both poetry and prose works. He lived in Paris from 1965 to 1979, and then between Morocco and France until his death in 1995. In 1968, he won the Jean Cocteau Prix des Enfants Terribles, which had been created to recognize original and provocative writers. Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine is one of the writers who can be credited with introducing new and original literary techniques to the Maghreb, techniques that are much in evidence in Agadir.

Agadir, Khaïr-Eddine’s debut prose work, was originally published in French in 1967. It is loosely based on the 1960 earthquake, which devastated the city of the title. Khaïr-Eddine worked for the Social Security Department, between 1961 and 1963, conducting surveys among survivors of the earthquake. Likewise, the narrator of the novel is a civil servant, sent to the city “in order to sort out a particularly precarious situation”. But the earthquake is a metaphor for much more. As Lyamlahy’s introduction to the novel tells us, Khaïr-Eddine’s aim was “to symbolise the political and social earthquake which has been devastating the Third-World for years”.

Through his text Khaïr-Eddine voices a violent criticism of patriarchy and power, both religious and political. The author’s friend, poet Jean-Paul Michel, has suggested that the author’s childhood experience of his father’s abandonment of him and his mother helps us to understand his revolt against patriarchy, many examples of which can be found in Agadir, which features multiple patriarchal figures (kings, imams and government ministers, some human, some, such as President Marmoset, in animal form) and ends in a dialogue with “His Father”. Historical, contemporary and legendary figures interact across time and space in Khaïr-Eddine’s text. The monarch, described as the “hydra of the era” by “Yusuf, the First King”, comes in for particularly harsh criticism: “His Majesty whose gift to me is terror”; “the king feeds off the blood of the people”. Indeed Khaïr-Eddine’s criticism of the monarchy led to his arrest on his return to Morocco in 1979.

Khaïr-Eddine intends to shock. He described his writing as a “guérilla linguistique”, which can be understood as a kind of “linguistic guerrilla warfare”, in which his poetics of violence is directed as much against the text itself as at the society it criticises.

Although fighting against many things, Khaïr-Eddine’s surreal text also advocates for change, for example in his consideration of how and where and whether the city be reconstructed: “MAYBE TO START WITH BUILD WELL-ALIGNED HOUSES ON ONE SIDE AND ON THE OTHER thus leaving a wide enough space between them” he suggests. But the debate rages on:

“I want to assist in the construction of this city

There won’t be any construction Listen to me The city has never

existed There was a lot of propaganda about it but there never was a city here”

The question of “if it is permitted to build on the ruins of a dead city” encompasses many of the issues that Agadir addresses in its unique way; questions of justice and authority, and of identity, memory, home and belonging. The narrator discusses ancestry with “The Stranger”, who describes himself as “the special envoi of Her Majesty, the Kahina” (a 7th century Amazigh queen who appears several times in Agadir):

“THE STRANGER

You certainly don’t lack disrespect for your ancestors.

I

So you are my ancestor. And that stone, it wouldn’t be my grandmother by any chance?

THE STRANGER

You are insulting yourself. That’s regrettable.”

Later, the statement “I am a writer”, precedes an imagined passport, where the name and nationality are blank (merely a question mark) but the holder’s profession is given as “Rebel”. This is followed by a pages-long poetic diatribe in the stream-of-consciousness style on blood and identity: “my blood I’ll have to croak some day, I slam shut the doors of my blood, in its quagmires I lose the Ruby of rubies, the Blood of bloods and the Worst of the worse, my publisher blood, my blood I exile myself with tons of turtle doves…”

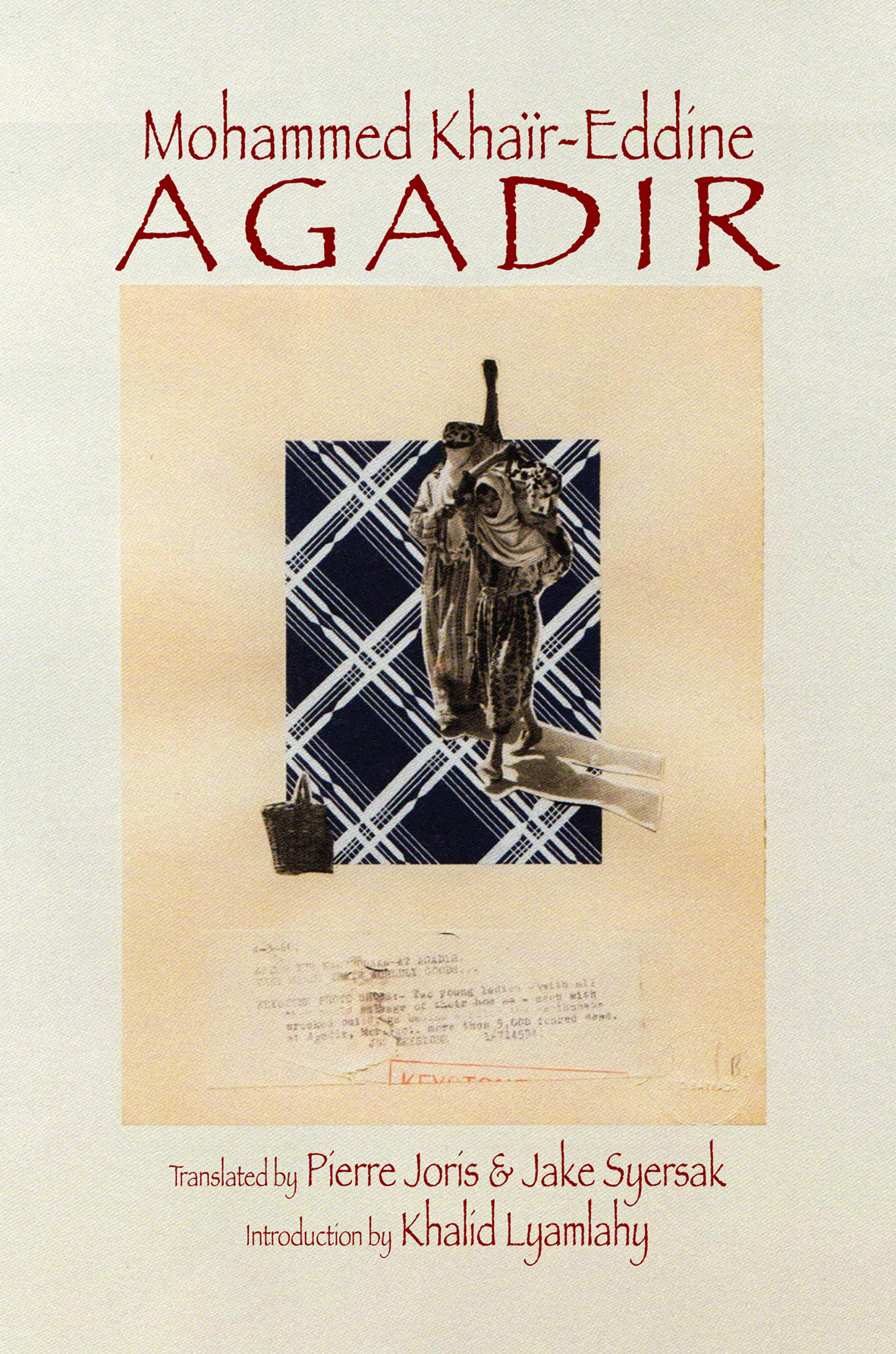

On the cover of the English edition of Agadir is a collage by Moroccan-French artist, Yto Barrada, inspired by Agadir. A collage is appropriate. Agadir is a literary collage, a work of art. A carefully constructed text that reads like a stream of consciousness, perhaps a reflection of the author’s belief that it is the writer who is possessed by the language, rather than vice versa*. Khaïr-Eddine’s word choice is very specific, often employing rare, exotic words; not mere rock but “schist”, not a generic wasp but a “sphex”, not just any old mosquito but “stegomyia”. The novel is bursting with interesting and thoughtful images. Sounds, smells and images are skilfully woven into the narrative: the “hyper-odor” of the “exhalations of croaked rats” in a city that “oozes a red and white-veined drop onto the misty terrain’s folds”.

The passages of dramatic dialogue are populated by a panoply of characters. Political debate and the problems of society are expressed in the voices of the narrator’s cook and servant, the townspeople, leaders past and present, real and legendary, and even animals. At one point the narrator finds himself in a surreal city populated by animals, somewhat reminiscent of Animal Farm.

In some passages, the stream of consciousness combined with a lack of punctuation evokes the disjointed, surreal nature of a dreamscape. And as in a dream, the scene suddenly changes. “We came at dawn. I don’t know why we’re here…We’re not in a street. In fact, I’m finding it impossible to make the place out.” In fact, the author has admitted to writing down his dreams and incorporating them into the narrative.

The aforementioned features of Khaïr-Eddine’s text must have made Agadir an interesting challenge for its translators. Khaïr-Eddine’s masterful and original manipulation of language has been cleverly translated into English by Pierre Joris, a Luxembourg-American writer who has published more than 50 books of poetry, essays, anthologies, plays and translations; and poet, translator and editor Jake Syersak, whose translation of another innovative Amazigh poet, Hawad, appears in Banipal 67.

The question of language is multi-faceted and interconnects with that of identity in Khaïr-Eddine’s work. An Amazigh, raised in a country whose official language was Arabic, he made a deliberate choice to write in French, delighting in subverting and reinventing it, playing with the language. Translation of Agadir is not a linear one-to-one practice. The text is Moroccan, incorporating Arabic and Amazigh words. The translation tends to keep these, reflecting the way they appear in the French text, and words for local Moroccan garments and concepts, such as gandoura, gimbri, choukkara, souk, raïs and caïd, appear in the text with no explanations. The translators have succeeded in bringing the text to the anglophone reader, without losing the essence of the original language. Indeed, Joris has written in his foreword to Scorpionic Sun, a collection of Khaïr-Eddine’s poetry, translated by Conor Bracken (Cleveland State University Poetry Center in 2019), that the reader wondering what the original French was is to be considered a good thing.

In addition to its innovative style, Francophone Moroccan literature of this era offers an insight into an important stage in Morocco’s cultural and political history. This translation helps to bring that literature to an anglophone audience. Disturbing, disquieting, but never boring, Agadir is a book that makes the reader work, think and question. It is not a book to read once but rather it is a work of art to return to again and again, each time discovering something new.

PUblished in Banipal 70 – Mahmoud Shukair, Writing Jerusalem